Canine transmissible venereal tumour (CTVT) was the

first naturally occuring neoplasm that is spread by the transferring

of cells from an affected dog to another. It happens to be venereally

transmitted. The second neoplasm to be spread in a similar fashion

is the oral facial tumour of Tasmanian devils, called Devil Facial

Tumour Disease. The tumours are therefore allographs. While this has been

known for many years, it has been definitively established by recent

molecular techniques. There are several reviews written about the

CTVT (Cohan 1978, Mukaratirwa and Gruys 2003, Mello-Martins et al

2005)

The cells of CTVT have a chromosomal number of 57,

58 or 59. The dog has 78. Weber et al (1965) examined the chromosomes

of CTVT in the USA, and they were nearly identical to those reported

in Japan. They suggested that the CTVT was a transplanted tumour

that arose from one dog. Dogs with the neoplasm spread it to other

dogs, so the tumour has always been regarded as an infectous tumour.

More recently, Murgia et al (2006) used molecular techniques to

identify that neoplasms from different continents and collected

decades apart are clonal, and, while there are 2 subtypes, they

have a common origin. The DNA of the CTVT has closely related DNA

of wolves and East Asian dog breeds.

The cells of a CTVT are able to avoid detection by

the immune cells. They downregulate class 1 molecules and there

is no class 2 activity, because they secrete inhibitory cytokines

(TGFbeta1 and IL 6) (Liao et al 2003, Murgia et al 2006). In the

initial proliferative phase of CTVT, they express little MHC Class

1 or 2. After about 12 weeks in an experimental model, MHC expression

increased dramatically and was associated with the presence of lymphocytes;

and at the same time, the masses stopped growing. It appeared that

the lymphocytes stimulated MHC expression and are responsible for

regression of the tumours (Hsiao et al 2002).

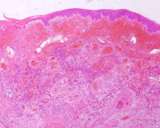

CTVT are usually found on the penis, but they are

occasionally seen in the mouth (Bright et al 1983), and metastasis

occurs to the skin and throughout the body, including the brain (subdural and extraaxial). There is one case of ocular CTVT. This occurs especially

in dogs that are immunosuppressed with whole body irradiation. It

is a rare occurrence naturally. One case of metastasis was found in the brain.

The phenotype of the cells have been the subject of

considerable debate over the years. They have features and staining

characteristics that suggest they are histiocytic in origin (see

below).

Dogs usually respond to treatment with vincristine. In one study of 38

dogs with CTVT, 31 responded to vincristine. One dog died, and 6 required

treatment with doxorubricin. There were no reoccurrences. (Nak et al 2005)

CTVT are also known to regress spontaneously, and there is evidence that host immunity is important in this and in progression. Paia et al (2011) enhansed regression by fusing allogenic dendritic cells with neoplastic cells and using them as a vaccine in affected dogs. Vaccinated dogs has reduced progression and enhanced regression over unvaccinated controls.

Stockman et al (2011) examined CTVT for the proteins p53, p63 and Bcl2, and found that all were present at all stages of the disease. These proteins are involved with induction of apoptosis.

Marino et al (2012) identified that dogs with leishmaniasis frequently had Leishmania organisms in macrophages in their tumours.

Murchison et al (2014) provides a state of the art publication on the genetics of CTVT.

Extragenital CTVT is more frequently seen in male dogs and in an oronasal locaton (

Macroscopic findings

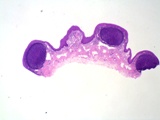

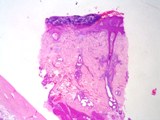

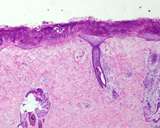

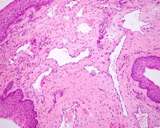

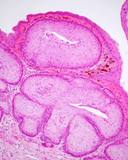

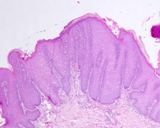

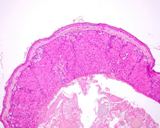

The lesions of transmissible venereal tumours are exophytic multinodular

proliferations in the preputial cavity, often attached to the junction

between the inner sheath of the prepuce and penile epithelium. The size

can vary considerably from small nodules to large fungating masses that

cause preputial swellings.

Figure : Transmissible venereal tumour, penis and prepuce

Microscopic findings

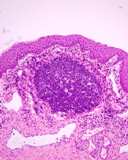

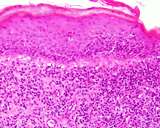

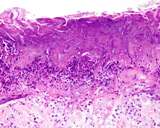

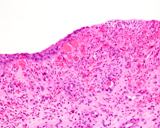

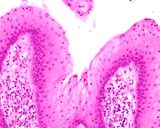

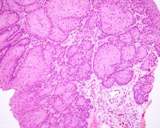

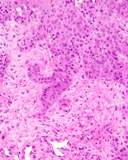

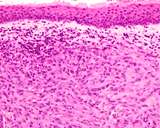

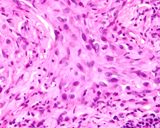

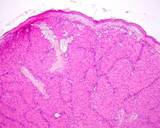

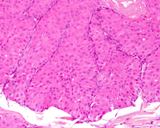

Transmissible venereal tumours are round cell tumours. They are locally

infiltrative, and the cells are often arranged in packets with a fine

stroma. The cells have well defined cytoplasmic boundaries, abundant often

clear cytoplasm and a central round to indented nucleus. Mitoses are numerous.

Some have fine vacuoles around the cytoplasmic membrane , and this feature

is particulary prominent in cytological specimens. Cells such as macrophages

and lymphocytes may be found in the neoplasms.

The differential diagnoses include lymphoma, histiocytic tumour, mast

cell tumour and plasmacytoma.

Immunohistochemistry

Sandusky et al (1997) stained 4 CTVT with S-100, kappa and lambda light

chains, alpha-1-antitrypsin, alpha-1-antichymotrypsin, LCA, neuron-specific

enolase, keratin, cytokeratin, muramidase, and vimentin. The CTVT were

consistently vimentin positive

Mozos et al (1996) reported on 25 CTVT stained for human lysozyme, human

alpha-1-antitrypsin, CD3, vimentin, human keratins, human lambda light

chains, canine immunoglobulins IgG, IgM, and S-100. Lysozyme was immunoreactive

in 10/25 alpha-1-antitrypsin in 14/25, and vimentin in 25/25 CTVT. All

were negative to keratins, S-100, lambda light-chain, IgG, IgM, and CD3.

Marchal et al (1997) reported CTVT stained for "lysozyme, ACM1 antigen,

vimentin, neuron-specific enolase, glial fibrillary acidic protein, desmin,

alpha smooth muscle actin, CD3, IgG, kappa and lambda light chains, and

keratin. Lysozyme immunoreactivity was detected in all cases, ACM1 antigen

in 11 of 14, neuron-specific enolase in 11 of 14, vimentin in 10 of 14,

glial fibrillary acidic protein in 4 of 14 and desmin in 1 of 14. All

the sections were negative to keratins, alpha smooth muscle actin and

CD3, whereas in five cases, perivascular tumour cells contained Ig G,

kappa and lambda light chains".

In summary then, CTVT are consistently vimentin positive, cytokeratin

and S100 negative round cell tumours that do not stain for specific T

or B lymphocyte markers and which stain for histiocytic markers.

Bright RM. Gorman NT, Probst CW, Goring CW. (1983) Transmissible venereal

tumor of the soft palate in a dog. J Amer Vet Med Assoc 183: 893-894.

Cohen D (1973) The biological behaviour of the transmissible venereal

tumour in immunosuppressed dogs. Europ J Cancer 9: 253-258

Cohen D (1978) The transmissible venereal tumor of the dog - a naturally

occurring allograft? a review. Israel J Med Sc 14: 14-19.

Dass LL, Sahay PN (1989) Surgical treatment of canine transmissible venereal

tumour - a retrospective study. Indian Vet J 66: 255-258.

Ganguly B, Das U, Das AK. Canine transmissible venereal tumour: a review. Vet Comp Oncol. 2016; 14: 1-12

Higgins DA (1966) Observations on the canine transmissible Venereal Tumour

as seen in the Bahamas. Vet Rec 79: 67-71.

Hsiao YW, Liao KW, Hung SW, Chu RM (2002) Effect of tumor

infiltrating lymphocytes on the expression of MHC molecules in canine

transmissible venereal tumor cells. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 87(1-2):19-27.

R. M. Kabuusu, D. F. Stroup, C. Fernandez (2010) Risk factors and characteristics

of canine transmissible venereal tumours in Grenada, West Indies. Vet

Comp Oncology 8: 50-55.

Liao KW, Hung SW, Hsiao YW, Bennett M, Chu RM (2003) Canine transmissible

venereal tumor cell depletion of B lymphocytes: molecule(s) specifically

toxic for B cells. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 92(3-4):149-162.

Marchal T, Chabanne L, Kaplanski C, Rigal D, Magnol JP.(1997) Immunophenotype

of the canine transmissible venereal tumour. Vet Immunol Immunopathol.

57(1-2):1-11.

Marino G, Gaglio G, Zanghì A. (2012) Clinicopathological study of canine

transmissible venereal tumour in leishmaniotic dogs. J Sm An Pract 2012,

Mello-Martins MI, Ferreira de Souza F, Gobello C (2005) Canine Transmissible

Venereal tumor: etiology, pathology, diagnosis and treatment. In: Recent

Advances in Small Animal Reproduction. Concannon PW, England G, Verstgegen

J, Linde-Forsberg (Eds) www.ivis.org.

Milo J, Snead E. A case of ocular canine transmissible venereal tumor.Can Vet J. 2014; 55: 1245-1249.

Mozos E, Mendez A, Gomez-Villamandos JC, Martin De Las Mulas J, Perez

J. (1996) Immunohistochemical characterization of canine transmissible

venereal tumor. Vet Pathol33(3):257-263

Mukaratirwa S, Gruys E. (2003) Canine transmissible venereal tumour:

cytogenetic origin, immunophenotype, and immunobiology. A review. Vet

Q. 25(3):101-111.

Murchison EP, Wedge DC, Alexandrov LB, Fu B, Martincorena I, Ning Z, Tubio JM, Werner EI, Allen J, De Nardi AB, Donelan EM, Marino G, Fassati A, Campbell PJ, Yang F, Burt A, Weiss RA, Stratton MR. Transmissible [corrected] dog cancer genome reveals the origin and history of an ancient cell lineage. Science. 2014; 24: 343, 437-440.

Murgia C, Pritchard JK, Kim SY, Fassati A, Weiss RA. (2006) Clonal origin

and evolution of a transmissible cancer Cell. 126(3):477-487.

Nak D, Nak Y, Cangul IT, Tuna B. (2005) A clinicopathological study on

the effect of vincristine on transmissible venereal tumour in dogs. J

Vet Med 52: 366-370.

Paia Chien-Chun, Kuob Tzong-Fu, Maoc Simon J.T. , Chuanga Tien-Fu, Lina Chen-Si, Chua Rea-Min (2011) Immunopathogenic behaviors of canine transmissible venereal tumor in dogs following an immunotherapy using dendritic/tumor cell hybrid Veterinary Immunology and Immunopathology 2011 139: 187–199

Parent R, Teuscher E, Morin M, Buyschaert A. (1983). Presence of the

canine transmissible venereal tumor in the nasal cavities of dogs in the

area of Dakar (Senegal). Canadian Vet J 24: 287-288.

Rogers KS, Walker MA, Dillon HB (1998) Transmissible venereal tumor:

a retrospective study of 29 cases. J Amer Anim Hosp Assoc 34: 463-470.

Sandusky GE, Carlton WW, Wightman KA. (1987) Diagnostic immunohistochemistry

of canine round cell tumors. Vet Pathol. 24(6):495-499

Stockmann D, Ferrari HF, Andrade AL, Cardoso TC, Luvizotto MCR. (2011) Detection of the tumour suppressor gene TP53 and expression of p53, Bcl-2 and p63 proteins in canine transmissible venereal tumour. Vet Comp Oncol 2011, 9: 251-259

Strakova A, Baez-Ortega A, Wang J, Murchison EP. Sex disparity in oronasal presentations of canine transmissible venereal tumour. Vet Rec. 2022 Jul 3:e1794.

Stockmann D, Ferrari HF, Andrade AL, Cardoso TC, Luvizotto MCR. (2011) Detection of the tumour suppressor gene

TP53 and expression of p53, Bcl-2 and p63 proteins in canine transmissible venereal tumour. Vet Comp Oncol 2011, 9: 251-259

Thornburn MJ, Gwynn RVR, Ragbeer MS, Lee BI. (1968) Pathological and

cytogenetic observations on the naturally occurring canine venereal tumour

in Jamaica (Sticker's tumour). British J Canccer 22: 720-727.

Weber WT, Nowell PC, Hare WCD (1965) Chromosome studies of a transplanted

and primary canine venereal sarcoma. J Nat Cancer Inst 35: 537-547.

Wright DH, Peel S, Cooper EH, Hughes DT. (1970) Transmissible venereal

sarcoma of dogs. A histochemical and chromosomal analysis of tumours in

Uganda. Rev Europ etudes Clin Et Biol 15: 155-160.