The testis descends into the scrotal sac by 10 days and certainly by 6

to 8 weeks. The initial phase of descent is the transabdominal phase and

is probably influenced by Anti-Müllerian hormone. The second phase

is the inguinoscrotal phase. During this phase, the inguinal canal expands

and the testis and epididymis move distally. The testes go through the inguinal

canal three to four (3-4) days after birth. Next the gubernaculums regresses

which draws the testicle into the scrotum. The testes are typically in its

final scrotal position in the scrotum by day 35. Because the inguinal canal

does not close until 6 months, it can potentially move back and forth.

Each testis and epididymis is arranged in a horizontal plane, with

the head slightly higher than the tail. The head is cranial and the tail

is caudal. The body of the epididymis is dorsal. The deferent duct is medial

to the body, and forms part of the spermatic cord (deferent duct, testicular

artery, vein and nerves). The spermatic cord is always dorsocranial.

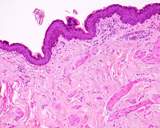

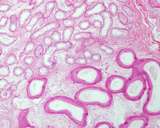

Figure 1. Normal testis and epididymis from a dog.

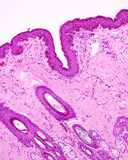

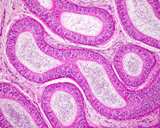

Figure 2. Normal testis and epididymis from a dog. Sectioned sagitally.

The efferent ductules and head of the epididymis are to the right, the

body is dorsal and the tail is to the left. The spermatic cord is intact

dorsally.

When sectioned sagitally, the testicular parenchyma is visible. The mediastinum

testis is central and there are fibrous bands that run radially from the

mediastinum. The normal colour is white pink. Spermatozoa should ooze

from the tail of the epididymis.

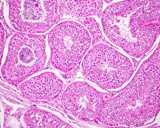

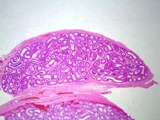

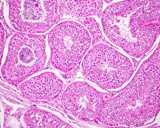

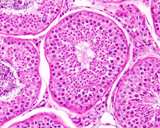

Histologically, the testis is similar to other that of other species.

The seminiferous tubules are coiled, but basically run from the rete testis

in the mediastinum to the tunica albuginea and back, this in a vertical

axis. A histological section taken from the tunic to the mediastinum will

often capture several cross sections of the same tubule.

Figure 3: Histology of a normal testis.

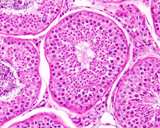

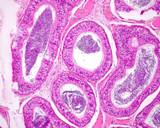

Figure 4: Histology of a normal testis.

The completely normal testis should have normal spermatogenesis in each

seminiferous tubule, however there are reports of otherwise normal dogs

with some degree of spermatogenic arrest or tubular degeneration. One

study (Rehm 2000) found that 30% of control beagles had bilateral segmental

degeneration or hypoplasia. Peters et al (2001) found no difference in

the diameter of the seminiferous tubules with age.

Inhibin alpha is expressed by Sertoli cells of prepubertal dogs, but the interstitial endocrine cells express it after puberty (Greico et al 2011).

The interstitial compartment of the testis has the interstitial endocrine

(Leydig) cells, blood vessels, and macrophages, dentritic cells, mast

cells, testicular T cells (in some species) and interstitial fibroblastic

cells.

Spermatozoa travel

from the seminiferous tubules, or more correctly the convoluted seminiferous

tubules to the straight seminiferous tubule into the rete testis. The

rete testis is a network of ducts in the mediastinum testis that are lined

by cuboidal epithelial cells. The intratesticular rete become the extratesticular

rete tubules and these become the efferent ductules. The efferent ductules

are lined by cuboidal and ciliated cells. The efferent

ductules number between 13 and 15. These are derived from the mesonephric

tubules.

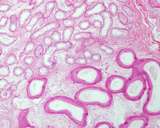

Figure 6: Normal efferent ductules

(upper left);,these number 13-15; compared to the head of the epididymis

(lower left, larger tube).

The efferent ductules join the

single epididymal (mesonephric) duct. Some may be blind ended, but this

is regarded as an 'anomaly' as it can lead to disease. The volume of fluid

entering the epididymis (called rete testis fluid) is large and much is

absorbed in the head of the epididymis.

Dym M. (1976)

The mammalian rete testis--a morphological examination. Anat

Rec 186(4):493-523.

Spermatogenic cycle and duration

Soares et al (2009) Performed a comprehensive study of the spermatogenic cycle and duration amongst multiple breeds. They found that the average spermatogenic cycle was 13.73 ± 0.03 days and the total duration was 61.9 ± 0.14 days.

Dogs have 8 stages of spermatogenesis, unlike most other species who have 12.

Soares JM, Avelar GF, França LR. (2009) The seminiferous epithelium cycle and its duration in different breeds of dog (Canis familiaris). J Anat 2009; 215: 462-471

Hormonal control

Inhibin is mostly produced by the interstitial endocrine cells, although it can secreted by both Sertoli and interstitial endocrine cells. Inhibin einhibits the release of follicle stimulating hormone from the pituitary gland and it also down regulates the activity of activin. Normal Sertoli cells in adult dogs do not appear to produce inhibin, however most Sertoli cell tumours do.

Activin is also produced by the interstitial endocrine cells and it modulates spermatogenesis and Sertoli cell function.

Marino G Zanghı A (2013) Activins and Inhibins: Expression and Role in Normal and Pathological Canine Reproductive Organs: A review. Anatomia Histologia Embryologia 2013,

Staining characteristics

In normal testes a clear

expression of IGF-I, IGF-II, IGF-IR, IGFBP2, IGFBP4 and IGFBP5 was found.

Expression of IGFBP1 and IGFBP3 was weak.

Warinrak et al (2014) stained the testis and epididymis for MMP 2 and MMP 9 and their inhibitors. They found these metalloproteinases in the germ cells of the seminiferous tubules.

The rete testis

expresses low molecular weight cytokeratin, desmin and vimentin (Wakui

et al 1994).

Wakui S, Furusato M,

Ushigome S, Kano Y. Coexpression of different cytokeratins, vimentin and

desmin in the rete testis and epididymis in the dog. J Anat. 1994 184

( Pt 1):147-51.

Warinrak C, Wu JT, Hsu WL, Liao JW, Chang SC, Cheng FP. (2014) Expression of Matrix Metalloproteinases (MMP-2, MMP-9) and their Inhibitors (TIMP-1, TIMP-2) in Canine Testis, Epididymis and Semen. Reprod Domest Anim. 2015; 50: 48-57.

Interstitial cells

- Calretinin

- Inhibin-alpha, -betaA, and -betaB chains and 3beta-HSD

- cKIT (CD117)

Sertoli cells

Germ cells

Spermatogonia are cKIT positive

Grieco V, Bancoa B, Giudicea

C, Moscaa F and Finazzia M (2010) Immunohistochemical Expression of

the KIT Protein (CD117) in Normal and Neoplastic Canine Testes. J Comp Pathol

2010, 142: 213-217

Grieco V, Banco B, Ferrari F, Rota A, Faustini M and Veronesi MC. (2011) Inhibin-a Immunohistochemical Expression in Mature and Immature Canine Sertoli

and Leydig Cells. Reprod Dom Animal 2011 46: 920-923

Radi ZA, Miller DL.(2005)

Immunohistochemical expression of calretinin in canine testicular tumours

and normal canine testicular tissue. Res Vet Sci. 79(2):125-129.

The prostate of the dog is the only accessory genital gland. Early reports

indicate 2 components - the bulbous part, and a disseminate part composed

of prostatic lobules in the wall of the urethra. Macroscopically, it is

a bilobed structure, and it increases in size with age. This hyperplasia

is discussed under 'Diseases of the Prostate'. The prostate of the Scottish

Terrier is larger than one would expect of a dog of that size.

Figure 10: Normal prostates from 2 dogs. A young, pubertal dog on

the left and an older dog on the right. The bladder is the lower

structure on each.

The normal histology of the prostate is complicated by the changes associated

with hyperplasia. Normal is a dynamic best dealt with in the section on

diseases.

The normal appearance of the prostate of 35 dogs was reported by Lee et al (2011)

Lee K-J, ShimizuJ, Kishimoto M, Kadohira M, Iwasaki T, MiyakeY-I, Yamada K (2011) Computed tomography of the prostate gland in apparently healthy entire dogs. J Small Anim Pract 2011 52: 146-151.

Immunohistochemistry

Acini

Grieco et al (2003) looked at intermediate filament expression of the

canine prostate. They used vimentin (3B4, V9) and cytokeratins AE1/AE3,

CK18-8 (for luminal cells), CK5, CK clone 8.12, CK14 (for basal cells). Normal prostatic

epithelia does not stain with vimentin. All stain with AE1/AE3, and

none with CK14. The others are variable.

| |

|

|

|

Basal cell |

Basal cell |

|

luminal cell |

luminal cell |

? acinar |

|

urothelium |

| |

Vimentin |

PanCK |

HMWCK

(1, 5 |

CK5 |

CK14 |

CK7 |

CK8 |

CK18 |

AR |

PSA |

Uroplakin III |

| ACINI |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Greico et al (2003) |

|

|

|

3/3 |

0/3 |

|

|

3/3 |

|

|

|

| Lai et al (2008) |

|

|

|

0/8 |

|

2/8 |

|

8/8 |

|

8/8 |

0/8 |

| Lai et al (2009) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2/2 |

|

|

| Ackers et al (2015) |

|

|

|

8/8 |

0/8 |

|

8/8 |

8/8 |

8/8 |

|

|

| PERIPHERAL DUCT |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Lai et al (2008a) intact |

|

|

2/8 |

5/8 |

0/8 |

1/8 |

|

7/8 |

|

6/8 |

0/8 |

| Lai et al (2008a) neutered |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Lai et al (2009) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2/2 |

|

|

| PERIURETHRAL DUCT |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Lai et al (2008a) intact |

|

|

3/8 |

6/8 |

0/8 |

1/4 |

|

8/8 |

|

6/8 |

1/8 |

| Lai et al (2008a) neutered |

|

|

3/3 |

3/3 |

0/3 |

3/3 |

|

3/3 |

|

3/3 |

2/2 |

| URETHRA |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Lai et al (2008a) intact |

|

|

3/8 |

8/8 |

0/8 |

6/8 |

|

7/8 |

|

6/8 |

8/8 |

| Lai et al (2008a) neutered |

|

|

1/2 |

2/2 |

0/2 |

2/2 |

|

2/2 |

|

2/2 |

2/2 |

Allen WE, Dagnall GJR (1982) Some observations on the aerobic bacterial

flora of the genital tract of the dog and bitch. J Small Anim Pract 23:

325-335.

Gunzel-Apel AR, Mohrke C, Poulsen Nautrup C. (2001) Colour-coded and pulsed

Doppler sonography of the canine testis, epididymis and prostate gland:

physiological and pathological findings. Reprod Domest Anim. 36(5):236-340

Lai CL, van den Ham R, van Leenders G, van der Lugt J, Teske E. Comparative characterization of the canine normal prostate in intact and castrated animals. Prostate. 2008 Apr 1;68(5):498-507

McEntee K (1990) Reproductive Pathology of Domestic Mammals. Academic Press,

Toronto.

Ninomiya H, Nakamura T. Vascular architecture of the canine prepuce. Anat Histol Embryol. 1981;10(4):351-60. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0264.1981.tb00699.x. PMID: 6462070.Peters MA, de Rooij DG, Teerds KJ, van de Gaag I, van Sluijs

FJ. (2001)

Spermatogenesis and testicular tumours in ageing dogs. J Reprod Fertil Suppl.57:419-21

Rehm S. (2000)

Spontaneous testicular lesions in purpose-bred beagle dogs. Toxicol Pathol

28: 782-787.