©All materials are copyright and should not be used without the expressed

permission of the author

The pathology, pathogenesis and salient features of

canine transmissible venereal tumour (CTVT) is recorded under disease

of the male (see CTVT).

Those features unique to the female are mentioned here.

Brody and Roszel (1967) reports on 10 CTVT in their series of neoplasms

of the genital tract.

Thacher and Bradley (1983) report 99 cases of vulvar and vaginal

tumours and found 10 transmissible venereal tumours. The neoplasms

are usually within the vestibule.

Ortega-Pacheco et al (2006) examined 300 stray bitches and found

that 15% had CTVT.

Park M-S et al (2006) reported on a case of CTVT that had widespread

metastasis.

Bastan et al (2008) report metstasis of canine transmissible venereal

tumour to the uterus and ovaries of a 7 year old dog . This boxer

had a vaginal CTVT.

There is only one case in the YagerBest

database, and that case was acquired outside Canada.

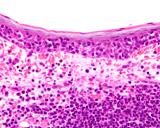

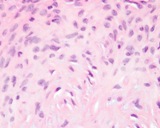

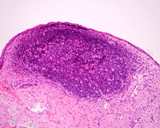

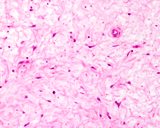

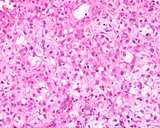

Figure : Canine transmissible venereal tumour.

The neoplastic cells are round, uniform and have a clear cytoplasm

with fine vacuoles at the periphery of the cells.

Bastan A, Baki Acar D, Cengiz M (2008) Uterine and ovarian metastasis

of transmissible venereal tumor in a bitch. Turk J Vet Anim Sci 32:

65-66

Brody RS, Roszel JF (1967) Neoplsms of the canine uterus, vagina

and vulva: a clinicopathologic survey of 90 cases. J Amer Vet med

Assoc 151: 1294-1307.

Park MS, Kim Y, Kang MS, Oh SY, Cho DY, Shin NS, Kim DY (2006) Disseminated

transmissible venereal tumor in a dog. J Vet Diagn Invest. 18(1):

130-133.

Ortega-Pacheco A, Segura-Correa JC, Jimenez-Coello M, Linde Forsberg

C. (2006) Reproductive patterns and reproductive pathologies of stray

bitches in the tropics. Theriogenology.

Thacher C, Radi RL (1983) Vulvar and vaginal tumors in the dog: a

retrospective study. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 183(6): 690-692.

Smooth muscle and fibrous tumours of the vagina of dogs, including

leiomyoma and fibroleiomyoma, are very common, and represent the most

common single lesion of the vagina. Despite this, there are very few

reports of them, apart from occasional surgical or clinical articles

(Kang and Holmberg 1983). The neoplasms are single or multiple, and

are seen almost exclusively in entire bitches. This has lead to the

suggestion that smooth muscle tumours may be hormonally responsive

and desexing is part of the management. This is further supported

by the identification of estrogen and progesterone receptors in the

stroma and smooth muscle of the vagina and vulva (as well as the epithelium)

of dogs (Vermeirsch et al 2002, Avallone et al (2022).

There are no established criteria to separate 'benign' and 'malignant' smooth muscle tumors that relates to clinical outcome.

Millan et al (2007) examined oestrogen and progesterone receptor

expression in canine reproductive smooth muscle tumours. They had

28 leiomyomas (4 uterine, one cervical, 15 vaginal, 6 vulval and 2

perineal), 3 fibroleiomyomas (2 vaginal, and one vulval) and 1 leiomyosaroma

(vulval). Two were spayed bitches. They used immunohistochemistry

to detect calponin to confirm the neoplasms were of smooth muscle

type and 29 of 32 were positive. These were stained to detect oestrogen

receptor alpha (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR). 18 of 32 were

ER positive and 27 of 32 were PR positive.

Ozmen et al (2008) reported a single case of multiple leiomyomas

in a bitch - they were in the uterus, cervix and vagina. Immunohistochemical

staining was done - they are muscle specific actin positive, pancytokeratin

and S100 negative, desmin was slightly positive.

Stiver et al (2019) reported on a case of vaginal leiomyoma in a dog with hypercalcemia. Hypercalcemia resolved with removal of the neoplasm.

Avallone et al (2022) reported on cases of smooth muscle tumor.

Macroscopic features

Benign stromal neoplasms of the vagina are similar in appearance

and histological assessment if needed to separate them. They are either

single or multiple and tend to be well circumscribed and explansile

nodules. Some are pedunculated and they become ulcerated on the mucosal

surface. They are usually white and tough. Vaginal stromal polyps

can have asimilar appearance.

Thacher and Bradley (1983) report 99 cases of vulvar and vaginal

tumours and found 26 leiomyomas and 27 fibromas.

Microscopic features

Histological assessment of the neoplasms is required to provide a

definitive diagnosis, but an individual neoplasm can be difficult

to categorise into leiomyoma, fibroleiomyoma or fibroma. This is because

they have a variable number of cells that phenotypically resemble

smooth muscle or fibrous tissue. Even differentiating fibromas from

stromal polyps can be difficult and some people group fibromas in

with the polyps.

Leiomyomas are predominantly composed of cells that resembe

smooth muscle. They have minimal fibrous stroma, are composed of cells

with well defined cytoplasmic boundaries with abundant pink cytoplasm

and oval nuclei that are regular in size and have vesicular chromatin.

Mitoses should be rare if present at all. The cells should be smooth

muscle actin positive.

Fibroleiomyomas are a mixture of smooth muscle and fibrous

tissue with abundant collagen.

Fibromas are composed of whirls and bundles of fibroblasts

and collagen arranged in an irregular and haphazard manner.

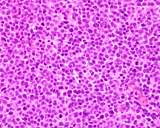

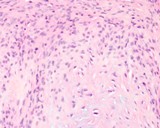

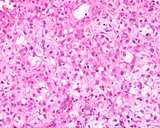

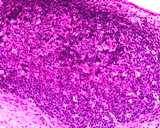

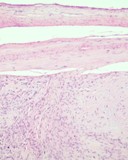

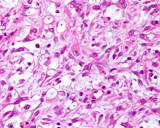

Figure : Fibroleiomyoma of the vagina. The combination

of neoplastic mesenchymal cells resembling mature smooth muscle cells

and abundant collagen as part of fibrous tissue is consistent with

fibroleiomyoma.

Avallone G, Pellegrino V, Muscatello LV, Roccabianca P, Castellani G, Sala C, Tecilla M, Valenti P, Sarli G. Canine smooth muscle tumors: A clinicopathological study. Vet Pathol. 2022; 59: 244-255.

Kang TB, Holmberg DL (1983) Vaginal leiomyoma in a dog. Can Vet J

24: 258-260.

Millan Y, Gordon A, Espinosa de los Monteros A, Reymundo C, Martin

de las Mulas J. Steroid receptors in canine and human female

genital tract tumours with smooth muscle differentiation. J Comp Pathol 2007;

136: 197-201

Ozmen O, Haligur M, Kocamuftuoglu M. (2008) Clinocopathologic and

Immunohistochemical Findings of Multiple Genital Leiomyomas and Mammary

Adenocarcinomas in a Bitch. Reprod Dom Animal. 43 (3): 377–381

Thacher C, Bradley RL (1983) Vulvar and vaginal tumors in the dog:

a retrospective study. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 183(6): 690-692.

Vermeirsch H, Van den Broeck W, Simoens P. (2002) Immunolocalization

of sex steroid hormone receptors in canine vaginal and vulvar tissue

and their relation to sex steroid hormone concentrations. Reprod Fertil

Dev 14(3-4): 251-258.

Stiver S, Laukkanen C, Luong R. Suspected Hypercalcemia of Benignancy Associated with Canine Vaginal Leiomyoma. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2019; 55: e55205.

Leiomyosarcoma

Leiomyosarcoma is the malignant counterpart of the leiomyoma.

The general features of vaginal and vulval leiomyosarcomas are

similar to leiomyomas. They may be multilobular, may have regions

of necrosis, and often are infiltrative. Their microscopic features

include the presence of greater anisokaryosis and mitoses are

present, and often above 15 pHPF. There are no established criteria to separate leiomyoma and leiomyosarcoma.

Thacher and Bradley (1983) report 99 cases of vulvar and vaginal

tumours and found 10 leiomyosarcomas. There are 4 in the YagerBest

database.

Avallone G, Pellegrino V, Muscatello LV, Roccabianca P, Castellani G, Sala C, Tecilla M, Valenti P, Sarli G. Canine smooth muscle tumors: A clinicopathological study. Vet Pathol. 2022; 59: 244-255.

Thacher C, Bradley RL (1983) Vulvar and vaginal tumors in the

dog: a retrospective study. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 183(6): 690-692.

Other mesenchymal neoplasms

Fibrolipoma

Haemangioma

Miller et al (2008) report finding 2 dogs with vaginal haemangiomas.

both had persistent vulval discharge. One dog was 11 and the other

was 18 months old. There were no photographs so we must rely on the

diagnosis by the pathologists involved. These ages seem very young

for a true neoplasm so we wonder if the lesions werent hamatomas (see

vascular hamartomas).

Miller JM, Lambrechts NE, Martin RA, Sponenberg DP, and Subasic M.

(2008) Persistent Vulvar Hemorrhage Secondary to Vaginal Hemangioma

in Dogs. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc44: 86-89

Haemangiosarcoma

Thacher and Bradley (1983) report 99 cases of vulvar and vaginal

tumours and found 1 haemangiosarcoma of the vulva.

Thacher C, Bradley RL (1983) Vulvar and vaginal tumors in the

dog: a retrospective study. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 183(6): 690-692.

Lipoma

Brody and Roszel (1967) report finding one lipoma of the vestibule.

Thacher and Bradley (1983) report 99 cases of vulvar and vaginal

tumours and found 4 lipomas. McEntee (1990) reports finding lipomas

of the vulva and vagina. There is one case in the YagerBest

database.

Brody RS, Roszel JF (1967) Neoplsms of the canine uterus, vagina

and vulva: a clinicopathologic survey of 90 cases. J Amer Vet med

Assoc 151: 1294-1307.

Thacher C, Bradley RL (1983) Vulvar and vaginal tumors in the dog:

a retrospective study. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 183(6): 690-692.

McEntee K (1990) Reproductive Pathology of Domestic Mammals. Academic

Press p 212.

Lymphangiosarcoma

Williams et al (2005) report a single case of a dog with pericervical

and pelvic lymphangiosarcoma that invaded the vaginal wall.

Williams JH, Birrell J, Van Wilpe E. (2005) Lymphangiosarcoma in

a 3.5-year-old Bullmastiff bitch with vaginal prolapse, primary

lymph node fibrosis and other congenital defects., J S Afr Vet Assoc.

76(3): 165-171.

Myxofibroma

Thacher and Bradley (1983) report 99 cases of vulvar and vaginal

tumours and found 1myxofibroma.

Thacher C, Bradley RL (1983) Vulvar and vaginal tumors in the dog:

a retrospective study. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 183(6): 690-692.

Myxoma

Thacher and Bradley (1983) report 99 cases of vulvar and vaginal tumours and found 1 myxoma.

Thacher C, Bradley RL (1983) Vulvar and vaginal tumors in the dog: a retrospective study. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 183(6): 690-692.

Osteosarcoma

Patnaik (1990) reported a case of primary osteosarcoma in the retrovaginal

tissues of a dog. Thacher and Bradley (1983) report 99 cases of vulvar

and vaginal tumours and found one osteosarcoma.

Thacher C, Bradley RL (1983) Vulvar and vaginal tumors in the dog:

a retrospective study. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 183(6): 690-692. Patnaik AK (1990) Canine extraskeletal osteosarcoma

and chondrosarcoma: a clinicopathologic study of 14 cases. Vet Pathol

27: 46-55

Nerve sheath tumour

Thacher and Bradley (1983) report 99 cases of vulvar and vaginal

tumours and found 3 peripheral nerve sheath tumours.

Thacher C, Bradley RL (1983) Vulvar and vaginal tumors in the

dog: a retrospective study. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 183(6): 690-692.

Neurofibroma

There is one report of a previously spayed dog that developed a vaginal mass that grossly was a large polyp. It was called a neurofibroma based on histological assessment, but there was no confirmatory immunohistochemistry 0r electron microscopy. The photomicrograph was unconvincing and I frankly dont believe it. The macroscopic and microscopic findings are typical of a vaginal polyp.

Sontas BH, Altun ED, Güvenc K, Arun SS, Ekici H.

(2009) Vaginal Neurofibroma in a Hysterectomized Poodle Dog. Reprod Dom Anim 2009 45: 1130-1133

Botryoid rhabdomyosarcoma

There is one case report of a vaginal botryoid rhabdomyosarcoma

in the literature (Suzuki et al 2006). This lesion was in

a 10 yr old dog, in the vestibule, and was surgically cured.

It was vimentin and desmin positive, and desmin positive by

immunohistochemistry. It was negative on PTAH histochemical

stain.

I have only seen one on these in the bitch. The bitch was

10 months old, and the lesion was treated surgically. Immunohistochemistry

was done - it was vimentin, actin and desmin positive, and

smooth muscle actin negative. PTAH was negative too.

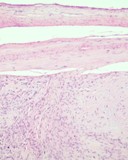

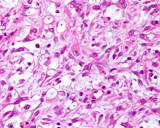

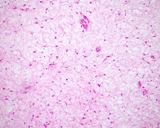

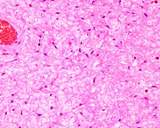

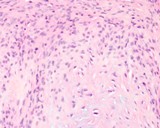

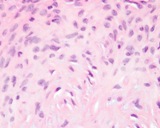

Figure : Vaginal botryoid rhabdomyosarcoma. The neoplasm is

an anaplastic sarcoma with large 'strap' cells resembling those

seen in rhabdomyosarcoma. Immunohistochemistry is required for

definitive diagnosis.

Suzuki K, Nakatani K, Shibuya H, Sato T. (2006) Vaginal rhabdomyosarcoma

in a dog. Vet Pathol 43(2): 186-188.

Carcinoma of the canine vestibule

This is an entity in the dog, but little is known of its pathogenesis.

It is believed to arise from the vestibule or to arise in the bladder

or urethra and spread to the vestibule. The lesion is visible as a

plaque or multinodular lesion of the vestibule and is often found

because of dysuria or hematuria. Histologically, they resemble transitional

cell carcinomas. As the epithelium of the bladder, urethra and vagina

all arise from the urogenital sinus, it is not surprising that neoplasia

of these areas has a similar phenotype. They are malignant tumours

and metastasis and death from disease is common. Those that grow near

the urethra especially affect urination and cause significant morbidity.

Brody and Roszel (1967) include one dog with an epidermoid carcinoma

of the vestible. It had not differentiation to squamous cells.

Roszel (1974) reported on metastatic mammary carcinomas with intralymphatic

metastases in the vestibule of 3 dogs.

Thacker and Bradley (1983) report finding 4 squamous cell carcinomas

and 1 adenocarcinoma of the canine vagina and vulva (the exact sites

were not indicated).

Magne et al (1985) reported 7 neutered bitches with carcinomas that

arose from the bladder or urethra and involved the vestibule or vagina.

The neoplastic cells were in the submucosa, and 4 were metastatic.

McEntee (1990) reports seeing 6 cases of carcinoma of the canine

vestibule. They arose from the ventral and lateral wall, and those

that were in the ventral floor near the urethra were assumed to have

arisen in the urethra.

There are 20 cases of carcinomas of the vestibule in the YagerBest

database.

Brody RS, Roszel JF (1967) Neoplasms of the canine uterus, vagina

and vulva: a clinicopathologic survey of 90 cases. J Amer Vet med

Assoc 151: 1294-1307.

Magne ML, Hoopes PJ, Kainer RA, Olson PN, Histed PW, Allen TA, Wykes

PM, Withrow SJ. (1985) Urinary tract carcinomas involving the canine

vagina and vestibule. J Amer Anim Hosp Assoc 21: 767-772

McEntee K (1990) Reproductive Pathology of Domestic Mammals. Academic

Press p 211

Roszel JF (1974) Canine metastatic mammary carcinoma in smears from

genital epithelium. Vet Pathol 11:20-28

Thacher C, Bradley RL (1983) Vulvar and vaginal tumors in the dog:

a retrospective study. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 183(6): 690-692.

Squamous cell carcinoma

Thacher and Bradley (1983) report 99 cases of vulvar and vaginal

tumours and found 4 squamous cell carcinomas.

There are 4 recorded in the YagerBest

database.

Thacher C, Bradley RL (1983) Vulvar and vaginal tumors in the dog:

a retrospective study. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 183(6): 690-692.

Sebaceous adenoma

There is one recorded in the YagerBest

database.

Adenocarcinoma of the clitoris

Neihaus et al 2010 report on a dog with an adenocarcinoma identical

to the apocrine adenocarcinoma of the anal sac that metastasised to

the internal iliac lymph nodes and produced hypercalcemia. Subsequently individual case reports were published by Mitchell et al (2012) and Rout et al (2016).

Verin et al (2018) then reported on 6 cases from multiple centers. They called this Canine Clitoral Carcinoma. Carcinomas of the clitoris in this study were adenocarcinomas of the apocrine glands of the region. All their dogs were spayed females. 3 of 5 dogs had regional lymphadenopathy of medial iliac and/or superficial inguinal nodes. 2 dogs were in clinical remission at 500 and 100 days. 3 were euthanased at 7, 150 and 180 days. 2 had hypercalcemia of malignancy. Histologically the carcinomas were of the tubular, solid, rosette or mixed types, just like the apocrine adenocarcinoma of the anal sac. Tumors were pancytokeratin positive, weak chromogranin A positive, some cells stained for synaptophysin, and all were NSE positive.

Piech et al (2019) provided the details of a single case that metastasised to draining lymph nodes and produced hypercalcemia.

Mitchell KE, Burgess DM, Carrigan MJ. Clitoral adenocarcinoma and hypercalcaemia in a dog.

Australian Veterinary Practitioner 2012; 42: 279-282.

Neihaus SA, Winter JE, Goring RL, Kennedy FA, Kiupel M. 2010: Primary

Clitoral Adenocarcinoma With Secondary Hypercalcemia of Malignancy

in a Dog. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2010; 46: 193-196.

Piech TL, Chu S, Bozynski CC, Royal AB. Pathology in Practice. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2019; 254: 1167-1170.

Rout ED, Hoon-Hanks LL, Gustafson TL, Ehrhart EJ, MacNeill AL. What is your diagnosis? Clitoral mass in a dog. Vet Clin Pathol. 2016; 45: 197-198.

Verin R, Cian F, Stewart J, Binanti D, MacNeill AL, Piviani M, Monti P, Baroni G, Le Calvez S, Scase TJ, Finotello R. Canine Clitoral Carcinoma: A Clinical, Cytologic, Histopathologic, Immunohistochemical, and Ultrastructural Study. Vet Pathol. 2018; 55: 501-509.

It is normal for the vagina and vestibule to swell with edema

during proestrus and oestrus. This edema subsides during metoestrus.

Excessive swelling occurs in some breeds (like the brachycephalic

breeds) and individuals. The folds of the vagina become expanded

and protrude caudally. It is usually the ventral floor of

the vagina that bulges and is visible. When it is excessive,

the vaginal mucosa may be visible from the vulva. This protrusion

of mucosa is not true prolapse, which is restricted to circumferential

protrusion of the vagina.

Biopsy of vaginal mucosa in this situation will show marked

oedema of the mucosa. With progressive oedema or chronicity,

fibrous tissue may develop from chronic or relapsing edema.

It is thought that, with time vaginal polyps develop.

The vagina will swell with hyperestrogenism from normal estrus,

estrogen secreting tumours or exogenous administration of

estrogen. Signs of estrus in a premature bitch may occur (Schwarze

and Threlfall 2008).

Antonov A, Atanasov A, Fasulkov I, Karadaev M. Clinical retrospective study of vaginal hyperplasia in the bitch (2012-2022). Reprod Domest Anim. 2023; 58: 1352-1358.

Johnston SD (1989). Vaginal prolapse Current Vet Therapy

p 1303-1305

Manothaiudom K, Johnston SD. (1991) Clinical approach to

vaginal/vestibular masses in the bitch. Vet Clin North Am

Small Anim Pract. 21(3):509-521.

Post K, Van Haaften B, Okkens AC (1991) Vaginal hyperplasia

in the bitch: Literature review and commentary Can Vet

J. 32(1): 35-37.

Schaefers-Okkens AC (2001) Vaginal edema and vaginal fold

prolapse in the bitch, including surgical management. In;

Recent Advances in Small Animal Reproduction, PW Concannon,

G English, J Verstegen. Eds International Veterinary Information

Service (www.ivis.org) Ithaca, New York.

Schwarze RA and Threlfall WR. (2008) Theriogenology Question

of the Month J Amer Vet Med Assoc 233 (2): 235-237.

Soderberg SF. (1986) Vaginal disorders. Vet Clin North Am

Small Anim Pract 16(3):543-559.

We restrict this section to inflammation of the vagina and vestibule,

and discuss inflammatory disease of the vulva and perivulval tissue under

vulvitis below.

Vaginitis is a clinical condition where there is a vaginal discharge

apart from at oestrus. and that contains neutrophils in numbers in excess

to those seen in oestrus. Not all cases will have true inflammation of

the vagina or vestibule, but many subsequently develop a change that would

be recognized as inflammation of the vagina.

It is widely believed that the presence of abnormalities of the vagina

and vestibule are responsible or or 'associated with' vaginitis, as these

anomalies are found in cases of vaginitis. For example, vestibulovaginal

stenosis is believed to predispose a bitch to vaginitis. Unfortunately

there are few comprehensive controlled studies that support these clinical

beliefs. A recent example is Wang et al (2006) who studied the widely

held belief that urinary tract disease was associated with vestibulovaginal

stenosis. They found that more normal dogs had stenosis than affected

dogs!

Johnson (1991) summarized the dogma regarding the potential causes of

vaginitis and they include

- infection

- immaturity

- chemical irritation from urine

- mechanical irritation from polyps, tumours

- anatomical anomalies

At the risk of propogating misinformation, we will suggest that clinical

vaginitis MAY POTENTIALLY occur in these main situations in dogs (even

though these may not withstand rigerous controlled studies.

- as a primary condition without apparent predisposing factors, most often

in prepubertal puppies,

- secondary to vaginal anomalies including conformational abnormalities

and polyps and tumours

- secondary to endometritis and 'open cervix' pyometra

(see disease of the canine uterus.)

- secondary to inflammation and or infection of the surgical site of ovariohysterectomy.

Vaginitis that occurs as part of endometritis and pyometra will be discussed

under disease of the canine uterus.

Vaginitis, regardless of the cause, will become chronic and the immunological

responses that ensue will cause lymphatic nodules (lymphoid follicles) to be enlarged and develop,

especially in the vestibule.

There are many clinical 'reviews' of vaginitis, as referenced below.

Barton CL. (1977) Canine vaginitis. Vet Clin North Am. 7(4): 711-714.

Crawford JT, Adams WM (2002) Influence of vestibulovaginal

stenosis, pelvic bladder, and recessed vulva on response to treatment

for clinical signs of lower urinary tract disease in dogs: 38 cases

(1990-1999). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 221(7): 995-999.

Johnson CA. Diagnosis and treatment of chronic vaginitis

in the bitch. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 21(3): 523-531.

Soderberg SF. (1986) Vaginal disorders. Vet Clin North

Am Small Anim Pract. 16(3): 543-559.

Jackson JA, Corstvet RE.(1975) Transmission and attempted

isolation of the etiologic agent associated with lymphofollicular hyperplasia

of the canine species. Am J Vet Res 36(08): 1207-1210.

Wang KY, Samii VF, Chew DJ, McLoughlin MA, DiBartola SP,

Masty J, Lehman AM. (2006) Vestibular, vaginal, and urethral relations

in spayed dogs with and without lower urinary tract signs. J Vet Intern

Med. 20(5): 1065-1073.

Primary vaginitis (including

prepubertal or puppy)

Primary vaginitis is probably an uncommon disease, as the natural defences

of the vagina including the squamous epithelium, flow of fluids at oestrus,

and natural flora provide nonspecific barriers and factors to prevent

infection and inflammation. Most cases of vaginitis have other associated

lesions.

Primary vaginitis occurs in puppies or prepubertal bitches and

is a self limiting disease that disappears with the onset of oestrus (Barton

1977). While not specifically proven, it seems likely that there is colonisation

of the vagina with bacteria that cause a transient inflammatory reaction

until the nonspecific protective factors develop.

Most cases of vaginitis have an underlying predisposing cause or factors

and these are discussed below under the agents that may be involved (or

not!).

An clinically acute lesion of the vagina will result in a reddened edematous

and sometimes haemorrhagic change to the vaginal epithelium. Focal ulceration

may be present. This lesion is seldom biopsied.

Barton CL. 1977 Canine vaginitis. Vet Clin North Am 7(4): 711-714.

Bacteria

There is a normal flora of bacteria in the vagina of bitches. The bacteria

found includes Escherichia coli, beta-hemolytic streptococci,

and Staphylococcus aureus and intermedias, and a myriad

of others. While these may be regarded as potentially pathogenic, their

envolvement in disease is debatable. Hirsh and Wiger (1977) found that

although these organisms are commonly found in clinically normal bitches,

more species of bacteria and greater numbers are found when there are

vaginal exudates.

Brucella canis is a recognized cause of primary bacterial endometritis

and vaginitis.

Bjurstrom L. (1993) Aerobic bacteria occurring in the vagina of bitches

with reproductive disorders. Acta Vet Scand. 34(1):29-34.

van Duijkeren E. (1992) Significance of the vaginal bacterial flora in

the bitch: a review. Vet Rec. 131(16): 367-369.

Hirsh DC, Wiger N. (1977) The bacterial flora of the normal canine vagina

compared with that of vaginal exudates. J Small Anim Pract 18(1): 25-30.

Osbaldiston GW. (1971) Vaginitis in a bitch associated with Haemophilus

sp. Am J Vet Res. Dec;32(12):2067-9.

Viruses

Many cases of canine herpesvirus infection of bitches are subclinical.

Experimental disease can cause a mild (Appel et al 1969) or severe vaginitis

(Hill and Mare 1974). The reported lesions include petechial and submucosal

haemorrhages, and the development of multiple lymphoid nodules.

Appel MJ, Menegus M, Parsonson IM, Carmichael LE. (1969) Pathogenesis

of canine herpesvirus in specific-pathogen-free dogs: 5- to 12-week-old

pups. Am J Vet Res. 30(12): 2067-2073.

Hill H, Mare CJ. (1974) Genital disease in dogs caused by canine herpesvirus.

Am J Vet Res. 35(5): 669-672.

Fungi including yeasts

Bloom (1954) mentions candidiasis (thrush) in dogs. It is a rare condition.

Bloom F (1954) Pathology of the dog and cat - The genitourinary

system, with clinical considerations. American Veterinary Publications,

Inc, Evanston Illinois. p352

Mycoplasma and Ureaplasma

Just like bacteria, the presence of Mycoplasms and Ureaplasma spp is

of debatable significance and a high percentage of normal dogs harbour

these microorganisms.

Doig PA, Ruhnke HL, Bosu WT. (1981) The genital Mycoplasma and Ureaplasma

flora of healthy and diseased dogs. Can J Comp Med. 45(3): 233-238.

Most cases of vaginitis in postpubertal animals are associated with other

conditions. Most of the predisposing conditions are assumed to be involved,

but few have faced the rigors of adequate statistical association and

it is unfortunate that no systematic study has been done of the normal

variation in anatomical structure and function. Most conditions have been

present for a considerable period of time and so the vaginitis that is

present tends to be chronic.

Johnson (1991) indicated potential causes of vaginitis and those that

are secondary include chemical irritation from urine, mechanical irritation

from polyps, tumours, and anatomical anomalies. Vaginal foreign bodies

are included in this group.

Hammel and Bjorling (2002) found that vulvoplasty to treat recessed

vulva resulted in an improvement or cure of vaginitis, suggesting

that conformational abnormalities of the vulva may predispose to vaginitis.

Vaginitis secondary to congenital anomalies

Wykes and Soderberg (1983) list congenital abnormalities of the vulva/vestibule

and vagina including

- anomalies from failure of the paramesonephric duct join

the urogenital sinus such as vertical septum, annular stricture and

double vagina

- secondary pouch - accessory vagina

- stenosis of vagina (vestibulovaginal stenosis)

These anomalies will be discussed in more detail below.

Anomalies and chemical and mechanical irritation of the vestibule or vagina

could alter the normal protective mechanisms including causing pooling or

failure of secretions or fluids to drain adequately.

Vaginal foreign body

Vaginal foreign bodies are rarely reported in dogs. They include the

remains of puppies (Snead et al 2009).

Crawford JT, Adams WM (2002) Influence of vestibulovaginal stenosis,

pelvic bladder, and recessed vulva on response to treatment for clinical

signs of lower urinary tract disease in dogs: 38 cases (1990-1999). J

Am Vet Med Assoc. 221(7): 995-999.

Johnson CA. (1991) Diagnosis and treatment of chronic vaginitis in the

bitch. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 21(3): 523-531.

Snead ES, Pharr JW, Ringwood BP, Beckwith J. (2009) Long-Retained Vaginal

Foreign Body Causing Chronic Vaginitis in a Bulldog. Journal Amer Anim

Hosp Assoc 46: 56-60.

Inflammation of the vulva and perivulval skin is known by

several names including skin fold pyoderma, perivulvar pyoderma, mucocutaneous

pyoderma of the vulva, perivulvar dermatitis, and intertriginous dermatitis.

Strictly speaking, mucocutaneous pyoderma occurs at the junction of the

mucous and cutaneous tissues, and vulvar skin fold pyoderma occur under

the fold. Both areas can be affected simultaneously.

Perivulvar dermatitis is a common condition, especially in

obese dogs and those dogs with prominent perivulvar skin fold that cover

the vulva (also called recessed vulva, or vulvar hypoplasia). It has been

associated with vestibulitis, vaginitis and urinary tract infection.

Resolution of dermatitis is often acheived with surgery to

remove the excessive skin folds (vulvoplasty, episioplasty) (Lighter et

al 2001, Hammel and Bjorling 2002).

The pathogenesis of perivulvar dermatitis is believed to be

similar to other mucocutaneous and skin fold pyodermas, with the presence

of excessive moisture, warmth and secretions and exudates providing a suitable

region and substrate for bacteria to proliferate. The complication of urine

and urine 'scald' is also present in this location.

Macroscopic lesions.

The affected area is swollen, red and may be malodourous.

The hair may be stained brown black and the skin hyperpigmented. An exudate

may be present. Ulceration can also be present.

Microscopic lesions

Histopathology of the lesions indicates a hyperplastic dermatitis

with a lichinoid infiltrate. In other words, the epidermis is hyperplastic

with acanthosis and orthokeratotic or patchy parakeratotic hyperkeratosis.

Superficial pustules and crusts may be present. Exocytosis of neutrophils

may be present. Some cases will have erosion, and spongiosis may also be

present. There is usually a band of inflammatory cells beneath the epithelium,

and it is mostly plasma cells and lymphocytes with clusters of neutrophils.

This band hugs the epithelium, but there is not an obvious attack on the

basement membrane or basal layer. Single dead cells ('apoptotic" cells)

and blurring of the basement membrane/basal layer is not a feature. In many

cases, differentiation can only be made on clinical grounds including response

to treatment for pyoderma.

Differential diagnosis

Perivulval dermatitis/mucocutaneous pyoderma should be differentiated

from localized/discoid lupus erythematosis of the vulva, and other immune

mediated diseases such as pemphigous, erythema multiforma/drug eruption

and contact hypersensitivity.

Dorn AS. (1978) Biopsy in cases of canine vulvar-fold dermatitis

& perivulvar pigmentation. Vet Med Small Anim Clin. 73(9):1147-1150.

Hammel SP, Bjorling DE. (2002) Results of vulvoplasty for

treatment of recessed vulva in dogs. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 38(1): 79-83.

Lightner BA, McLoughlin MA, Chew DJ, Beardsley SM, Matthews HK. (2001)

Episioplasty for the treatment of perivulvar dermatitis or recurrent urinary

tract infections in dogs with excessive perivulvar skin folds: 31 cases

(1983-2000). J Am Vet Med Assoc 219(11): 1577-1581

Immune mediated dermatitis

Differentiating pyoderma from immune mediated disease of the lupus type

can be very difficult, or impossible. The main feature of the immune mediated

diseases is death of basal cells and a cellular attack on components of

the epithelium. If there is extensive distruction of the basal layer and

infiltration of the epithelium with lymphocytes, and acantholysis, then

immune mediated disease should be considered. Dermatopathology texts are

particularly good in their differentiation of the various types. Sometimes

the surgical pathologist can only suggest that the diseases be differentiated

based on clinical grounds including the response to appropriate therapy.

Miscellaneous dermatoses

McEntee (1990) reports seeing Demodex mites in the labial skin.

McEntee K (1990) Reproductive Pathology of Domestic Mammals. Academic press

p 205.

A recessed vulva is when the vulva is surrounded by perivulval

skin that extends past the labia. There is no accurate definition or measure

that determines exactly when a vulva is recessed, and the position of the

vulva relative to the pelvis is not assessed. It may be that the perivulval

skin folds become excessive so the 'recession' of the vulva may be relative

to the skin. It is a clinically recognized condition that is particularly

identified when a dog licks at the vagina, has incontinence, vaginitis,

perivulval dermatitis or other sign indicating inflammation or irritation

of the area. Other names for this condition include vulval hypoplasia

The pathogenesis is not proven, but early ovariohysterectomy

was an accepted predisposing situation. Obesity so that the perivulval skin

folds are exaggerated, is also implicated. Hammel and Bjorling (2002) studied

dogs with recessed vulva and underwent vulvoplasty, where the perivulval

folds were removed. They found that 7 of 34 dogs were intact yet still had

a recessed vulva, so early ovariohysterectomy is not a cause in all cases.

Ovariohysterectomy does affect the conformation of the vulva, especially

when surgery is done during the prepubertal period. There was not sufficient

information to assess the effect of obesity in their study.

Recessed vulva is implicated in urinary incontinence, urovagina,

vaginitis and perivulval dermatitis. The effect of vulvoplasty in the study

by Hammel and Bjorling (2002) was to eliminate vaginitis and perivulval

dermatitis suggesting that conformational factors predispose bitches to

these diseases.

It is suggested that a 'recessed' vulva prevents complete

elimination of urine, and that urovagina may develop. This and the fold

of skin around the vulva would predispose to inflammation and pyoderma.

Crawford and Adams (2002) found that dogs with a recessed

vulva also was likely to have severe vestibulovaginal stenosis. Dogs with

vaginitis responded to vulvoplasty if there was not severe stenosis. Likewise,

Lighter et al (2001) found that surgery to remove the skin folds resulted

in resolution of the perivulvar dermatitis and chronic urinary tract infection

associated with this.

A recessed vulva is a common condition. Wang et al (2006)

reported on 19 dogs with urinary tract disease and 12 normal dogs. 3 of

the normal and 10 of the clinically affected dogs had recessed vulvas.

Crawford JT, Adams WM (2002) Influence of vestibulovaginal

stenosis, pelvic bladder, and recessed vulva on response to treatment for

clinical signs of lower urinary tract disease in dogs: 38 cases (1990-1999).

J Am Vet Med Assoc. 221(7): 995-999.

Hammel SP, Bjorling DE. (2002) Results of vulvoplasty for

treatment of recessed vulva in dogs. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 38(1): 79-83.

Lightner BA, McLoughlin MA, Chew DJ, Beardsley SM, Matthews

HK. (2001) Episioplasty for the treatment of perivulvar dermatitis or recurrent

urinary tract infections in dogs with excessive perivulvar skin folds: 31

cases (1983-2000). J Am Vet Med Assoc 219(11): 1577-1581

Wang KY, Samii VF, Chew DJ, McLoughlin MA, DiBartola SP, Masty

J, Lehman AM. (2006) Vestibular, vaginal, and urethral relations in spayed

dogs with and without lower urinary tract signs. J Vet Intern Med. 20(5):

1065-1073.

Stenosis of the junction of the vestibule and vagina

(also called the cingulum) is when this area is narrow. This is

actually very common. The vestibulovaginal junction is the location

where the embryonic paramesonephric ducts join the urogenital sinus.

Stenosis of the cingulum occurs with either a remnant of the hymen

(annular fibrous band), or a true narrowing of the vagina

(vaginal hypoplasia).

Vestibulovaginal stenosis is a condition widely believed to be

involved with numerous clinical situations including recurrent or

chronic urinary tract infection, incontinence, failure to mate,

chronic vaginitis, and inappropriate urination (Kyles et al 1996).

There is, however, a wide variation in the diameter of the vagina

especially at the vestibulovaginal junction. Radiographical measurement

of the ratio of the diameter of the vestibulovaginal junction and

the vagina quantitates this in a wide range of breeds with differing

body sizes. A vestibulovaginal ratio of <0.33 (Holt 1985) is

used to indicate stenosis but no large scale study of normal dogs

has been done to show the range of normal. Wang et al (2006) examined

dogs and found that normal dogs had a mean vestibulovaginal ratio

of 0.313 and that those with clinical urinary tract signs had an

average of 0.357! They suggested that the criteria for diagnosing

vestibulovaginal stenosis be revisited.

The 2 main causes of vestibulovaginal stenosis are annular ring

(persitent perforate hymen) and true vaginal hypoplasia (Holt

and Sayle 1981). Most cases are though to be hypoplasia, but

this is probably a misnomer.

Holt and Sayle (1981) reported on 22 cases of vestibulovaginal

stenosis that involved a variety of breeds and found that had the

clinical signs including incontinence, vaginitis and mating difficulties.

Holt (1985), using the vestibulovaginal ratio of 0.33 found that

11 of 42 normal bitches and 12 of 57 dogs with incontinence had

stenosis.

Kyles et al (1996) reported on 18 dogs diagnosed with vestibulovaginal

stenosis, their selection critera included dogs with "annular

constriction of the vestibulovaginal junction cranial to the urethral

papilla".

Crawford and Adams (2002) correctly questioned the diagnosis of

vestibulovaginal stenosis with a vestibulovaginal ratio of <0.33.

They found that bitches with a ratio of <0.2 were more likely

to have unsuccessful treatment, but that marked stenosis may simply

be incidental.

Using the figures supplied by Wang et al (2006), all dogs have

some degree of narrowing at the vestibulovaginal junction that is

the upper range of the vestibulovaginal ratio in clinically normal

dogs was 0.48 and of clinically affected dogs was 0.60. The mean

ration was 0.313 and 0.357 for normal and affected animals respectively

and therefore close to or below the 0.33 that was defined as stenotic.

If the lowest value of 'normal' was 2 standard deviations below

the mean, then the cutoff between normal and abnormal would be a

ratio of 0.15 for normal and 0.16 for affected.

Clearly, a large number of normal dogs should be examined, and

followed prospectively for clinical signs. At the very least, any

stenosis not associated with interference with fluid flow from the

uterus should be treated as being 'normal'.

Crawford JT, Adams WM (2002) Influence of vestibulovaginal stenosis,

pelvic bladder, and recessed vulva on response to treatment for clinical

signs of lower urinary tract disease in dogs: 38 cases (1990-1999).

J Am Vet Med Assoc. 221(7): 995-999.

Holt PE, Sayle B. (1981) Congenital vestibulo-vaginal stenosis in

the bitch. J Small Anim Pract. 22(2): 67-75.

Kyles AE, Vaden S, Hardie EM, Stone EA. (1996) Vestibulovaginal stenosis

in dogs: 18 cases (1987-1995). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 209(11): 1889-1893.

Wang KY, Samii VF, Chew DJ, McLoughlin MA, DiBartola SP, Masty J,

Lehman AM. (2006) Vestibular, vaginal, and urethral relations in spayed

dogs with and without lower urinary tract signs. J Vet Intern Med.

20(5): 1065-1073.

Prolapse is from a latin word meaning to slip or fall

out of place. Protrusion of the vagina through the vulva occurs either

partially or circumferentially. Partial protrusion of the vagina, secondary

to edema during proestrus is covered under vaginal

edema and protrusion (hyperplasia, hypertropy, 'prolapse'). True

vaginal prolapse, where there is circumferential protrusion of the vaginal

wall, is a rare disease. It occurs after forcible separation of the

male, male disproportionate size (Bloom 1954), and as an incidenal condition.

Williams et al (2005) reported a dog that had vaginal prolapse secondary

to a lymphangiosarcoma of the vagina and pelvic tissues. Payan-Carreira et al (2012) reported on a dog with vaginal prolapse and uterine horn ruture.

Bloom F. (1954) Pathology of the dog and cat - The genitourinary

system, with clinical considerations. American Veterinary Publications,

Inc, Evanston Illinois. p328.

Manothaiudom K, Johnston SD. (1991) Clinical approach

to vaginal/vestibular masses in the bitch. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim

Pract. 21(3): 509-521.

Memon MA, Pavletic MM, Kumar MS. (1993) Chronic vaginal

prolapse during pregnancy in a bitch. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 202(2): 295-297.

McNamara PS, Harvey HJ, Dykes N. (1997) Chronic vaginocervical

prolapse with visceral incarceration in a dog. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc

33(6): 533-536.

Payan-Carreira R, Albuquerque C, Abreu H, Maltez L (2012) Uterine Prolapse with Associated Rupture in a Podengo Bitch. Reprod Dom Anim 2012, 47: 51–55

Williams JH, Birrell J, Van Wilpe E. (2005) Lymphangiosarcoma

in a 3.5-year-old Bullmastiff bitch with vaginal prolapse, primary lymph

node fibrosis and other congenital defects., J S Afr Vet Assoc. 76(3):

165-171.

Varices are dilated vessels that are also known as varicoceles. In rabbits

they are a well recognized lesion wherein they are are called endometrial

venous aneurysms.

Daugherty et al (2006) reports on a dog that had dilated vessels in multiple

organs including the vaginal submucosa.

Beccaglia et al (2008) reports the presence of a mass in the vagina of

a 3 year old pug dog that was well circumscribed and was composed of multiple

vascular channels. they considered this lesion a hamartoma, in part because

it contained nerves.

The 2 cases of haemangiomas reported by Miller et al (2008) may also be

hamartomas, as they occurred in young bitches.

Gower et al (2008) reports on a case of a 6 year old dog that had a history

of persistent vaginal hemorrhage. The distal vagina was excised and vaginal

vascular ectasia with thrombosis was found.

There is one case in the YB database.

Beccaglia M, Battocchio M, Sironi G and Luvoni GC (2008) Unusual Vaginal

Angiomatous Neoformation in a 3-year Old Pug. Reprod Domestic Anim 44: 144–146

Daugherty MA, Leib MS, Lanz OI, Duncan RB. (2006). Diagnosis and surgical

management of vascular ectasia in a dog. JAVMA 229: 975-979.

Gower JA, Schoeniger SJ, Gregory SP. (2008) Persistent vaginal hemorrhage

caused by vaginal vascular ectasia in a dog. J Amer Vet Med Assoc 233: 945-949.

Miller JM, Lambrechts NE, Martin RA, Sponenberg DP, and Subasic M. (2008)

Persistent Vulvar Hemorrhage Secondary to Vaginal Hemangioma in Dogs. J

Am Anim Hosp Assoc44: 86-89