Infection of the uterus may be more common than realised and not

all infection leads to inflammation. Natural protective mechanisms

such as uterine contraction and fluid and mucus production eliminates

infection in most circumstances. Ishiguro et al (2006) found that

the adhesion of E coli to endometrial cells was inhibited by Muc1,

and integral membrane mucin. Adherence of bacteria to the endometrium

was reduced during proestrus and estrus, and increased in the early

phase of dioestrus, which corresponds to the time of implantation.

This corresponds with the the expression of Muc1, and the reduction

of expression during dioestrus.

The uterus is prone to maintain infection if the nonspecific mechanisms

fail, and especially during the dioestral phase of the cycle. It is

during dioestrus that the dominant hormone is progesterone, and that

progesterone inhibits immunity in the uterus. Endometrial hyperplasia

may not, by itself, predispose the uterus to pyometra, rather endometrial

hyperplasia and pyometra may occur for a similar underlying reason.

Dow (1957), when describing the complex called the cystic hyperplasia-pyometra

complex found 23 of 100 dogs with CEH but no inflammation. Six of

these had E. coli recovered from their uteri, indicating a subclinical

infection. There were also 17 animals with CEH, but they had plasma

cells in the stroma. Antigen recognition was occurring, but the source

of the antigen was not known. Subclinical infection is possible. Dow

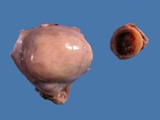

had 49 bitches with obvioius endometritis and pyometra. These had

a variable amount of pus in the lumen, the amount varying with the

degree of patency of the cervix. Three were unilateral. No bacteria

were found in five cases, E coli was isolated in all but 4 of the

remainder. Staphlococci and streptococci were isolated from a small

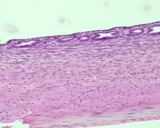

number. Fourteen cases were called chronic endometritis. Those with

a closed cervix had massive dilation of the uterus, and a wall that

was very atrophic and glands were often absent and the surface had

squamous metaplasia. When the cervix was open, the endometrium was

atrophic and glands were rare. There was fibrosis and numerous lymphocytes

and plasma cell were abundant. In 1958, Dow reported additional cases

300, and they were categorised in a similar way. Results were similar.

In 1959 Dow (1959) used the hormones estrogen and progesterone to

induce CEH and endometritis in ovarectomised dogs. Dogs given cycles

of estrogen followed by progesterone developed CEH and endometritis.

The endometritis was dominated by neutrophils in the stroma and epithelium,

and when progesterone was withdrawn, there was a change to plasma

cell accummulation, and to resolution of inflammation. This occurred

in cases where the uterus was isolated by a ligature around the distal

part of a horn. The reaction was identical to that see when no ligature

was present. Endometritis was clearly associated with the presence

of progesterone - especially the neutrophilic response. Plasma cells

dominated in uteri of dogs when progesterone therapy was stopped.

In most cases, E coli was isolated from inflammed uteri.

Hadley and Osbourne (1974) reviewed the pathophysiology of pyometra.

They recognised hormonal and bacterial factors. Pyometra occurs in

dioestrus when the uterus is influenced by progesterone. Progesterone

causes endometrial proliferation and secretion, and provides an environment

for bacterial proliferation. They considered that bacteria were secondary

invaders that were not necessary for the development of pyometra and

therefore complicate the disease, rather than initiated it!

Hadley (1975) found that the serum oestrogen and progesterone concentration

was within normal limits in single samples collected from dogs with

false pregnancy and in dogs with pyometra.

Nomura (1983) induced endometritis experimentally by infusing the

uterus with E coli from a case of pyometra in dogs at oestrus. Arora

et al (2006) ovarectomised dogs and used one cycle of hormones and

infused Escherichia coli to experimentally induce pyometra.

De Bosschere et al (2002) found that in endometritis-pyometra, estrogen

receptors (ER) were lower in expression and progesterone receptors

(PR) were higher in expression than in cystic endometrial hyperplasia,

suggesting that ER and PR expression was different and that the pathogenesis

was different. They suggested the presence of bacteria was the most

important factor, rather than the widely held view that endocrine

factors were the primary factors and bacterial infection was secondary

(Kivisto et al 1977)

It is known that dogs with pyometra due to E coli develop anti E

coli anitbody specific to the strain of E coli that infects the individual

uterus (Kivisto et al 1977, Borresen and Naess 1977). What part these

play in the pathogenesis is not known.

Schlafer and Gifford (2008) reviewed cystic endometrial hyperplasia

and pyometra.

Maddens et al (2010) evaluated renal function in bitches with pyometra with E coli and identifed that the clinical signs of renal dysfunction were the result of a transient glomerular and proximal tubular dysfunction.

Bartoskova et al (2012) examined the number and percentages of B cells, T cells, T-helper cells, cytotoxic T cells and gamma delta T cellsin the uterine of normal dogs and those with pyometra. The percentages and ratios of B and T cells did not change but there were was a marked increase in the number of gamma delta T cells in pyometra. CD8- gamma delta T cells were particularly prominent. Neutrophils were the dominant cell population. There was a regulation a pro-inflammatory cytokines and down-regulation of inhibitory cytokines.

England et al (2012) studied normal dogs and those affected with endometrial hyperplasia examining mating induced endometrial inflammation (which is predominantly neutrophilic) and the attachment of spermatozoa to the epithelium. They found that mating induced endometritis occurs in bitches, and there is reduced adherence of spermatozoa to the endometrium of bitches with endometrial hyperplasia.

Yasunaga et al ( 2013) examined the vaginal and uterine mucosa for the presence of glucose and mannose using lectins and found that dogs with pyometra had altered expression during days 7-10 adn 30-40 of diestrus. They surmised this variance was linked to the susceptibility of some dogs to develop pyometra.

Holsta et al (2013) recorded alterations in the function of phagocytes in the later phases of dioestrus that may contribute to pyometra.

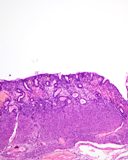

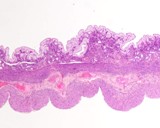

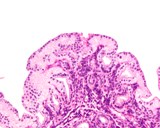

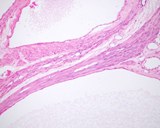

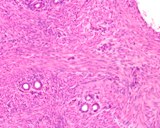

In most cases of endometritis, the histological lesions begin with

a migration of neutrophils and sometimes eosinophils into the glands and the lumen. Lymphocytes

and plasma cells will form in the stroma of the endometrium. With

a greater severity, particularly if the bacteria are toxigenic, there

will be erosion and ulceration of the endometrium. Some cases just

continue to accumulate neutrophils and the lumen will be tremendously

dilated. The endometrium will not be so severely affected, and in

some animals, squamous metaplasia will develop. The wall may become

atrophic.

While neutrophils predominate, some cases have large numbers of granulated

polymorphonuclear cells that resemble eosinophils.

In endometritis caused by Brucella canis the lesion is of

a lymphohistiocytic type (Brennan et al 2008).

Mir et al (2013) reported on the findings of 21 bitches with either not confirmed pregnancy or unexpected pregnancy loss biopsied by laparotomy. Six of the 11 bitches with lesions and endometrial fibrosis, four had endometritis and to had cystic endometrial hyperplasia. Two had localised endometrial hyperplasia (PEH). A mixture of lesions were seen in 4 of the 11 with histological lesions.No bitches had bacteria recovered from the uterus.

Gifford at al (2014) reported on 399 cases where some fertile bitches had full thickness endometrial biopsies. They reported on the full range of lesions present in the uterus. 170 (43%) of cases had endometritis. Of these one half (52%) had a predominantly lymphocytic or lymphocyte and plasma cell population, 30% had a combination of neutrophils, lymphocytes and plasma cells, and the remaining 18% had predominantly neutrophils, eosinophils (7%) or both. Of the 399 cases, 101 or 25% had fibrosis. Cystic endometrial hyperplasia was identified in 133 of the 399 (33%). Predicting breeding outcome of dogs with various types of endometritis and fibrosis is a work in progress.

McRae et al (2025) examined the endometrium histologically from 103 dogs at caesarian section (their fertile group) and 263 samples from subfertile bitches (those that did not become pregnant or had reduced litter sizes or resorptions). Samples were full thickness biopsies. While the material from the caesarian group is not exactly a control for samples collected in the same manner as the subfertile dogs, it does provide some reference. They found that dogs in the subfertile group with lymphocytes and plasma cells had a significantly different outcome than those in the caesarian group. Lymphocytes and plasma cells were present in the caesarian group - 58% had them vs 75% of those in the subfertile group. Older dogs had more than younger dogs. Neutrophils, eosinophils and histiocytes were similar in both groups. The presence of fibrosis and cysts was similar between them. There were many with eosinophils!

Arora N, Sandford J, Browning GF, Sandy JR, Wright PJ.(2006)

A model for cystic endometrial hyperplasia/pyometra complex in the

bitch.Theriogenology. 66(6-7): 1530-1536.

Baba E, Hata H, Fukata T, Arakawa A (1983). Vaginal

and uterine microflora of adult dogs. Amer J Vet Res 44: 606-609.

Bartoskova A, Turanek-Knotigova P, Matiasovic J, Oreskovic Z, Vicenova M, Stepanova H, Ondrackova P, Vitasek R, Leva L, Moore PF, Faldyna M. (2012) Gamma delta T lymphocytes are recruited into the inflamed uterus of bitches suffering from pyometra. The Vet J 2012 194: 303-309

Borresen B, Naess B (1977) Microbial, immunological

and toxicological aspects of canine pyometra.Acta Vet Scand 18: 569-571

Brennan SJ, Ngeleka M, Philibert HM, Forbes LB, and

Allen AL (2008) Canine brucellosis in a Saskatchewan kennel. Can Vet

J. 49(7): 703-708.

De Bosschere H, Ducatelle R, Vermeirsch H, Simoens P,

Coryn M (2002) Estrogen and progesterone receptor expression in cystic

endometrial hyperplasia and pyometra in the bitch. Animal Reprod Sc

70: 251-259

Dow C (1957). The cystic hyperplasia-pyometra complex

in the bitch. Vet Rec 69: 1409-1415

Dow C (1958) The cystic hyperplasia-pyometra complex

in the bitch. Vet Rec 70: 1102-1109

Enginler SO, Ate A, Diren Sıgırcı, B, Sontas BH, Sonmez K, Karacam E, Ekici H, Evkuran Dal G, Gurel A. (2014) Measurement of C-reactive protein and Prostaglandin F2a Metabolite Concentrations in Differentiation of Canine Pyometra and Cystic Endometrial hyperplasia/

Mucometra. Reprod Dom Anim 2014 49: 641-647Dow C (1959) Experimental reproduction of the cystic

hyperplasia-pyometra complex in the bitch. J Pathol Bacteriol 78:

267-278.

England GCW, Burgess CM, Freeman SL. (2012) Perturbed sperm–epithelial interaction in bitches with mating-induced endometritis. The Vet J 2012, 194: 314-318.

England GCW, Russo M, Freeman S (2013) The bitch uterine response to semen deposition and its modification by male accessory gland secretions. The Vet J 2003, 195: 179-184

Fransson B, Lagerstedt AS, Hellmen E, Jonsson P. (1997)

Bacteriological findings, blood chemistry profile and plasma endotoxin

levels in bitches with pyometra or other uterine diseases. Zentralbl

Veterinarmed A. 44(7): 417-426

Gibson A, Dean R, Yates D, Stavisky J (2013) A retrospective study of pyometra at five RSPCA hospitals in the UK: 1728 cases from 2006 to 2011 Vet Rec 2013; 173: 396

Gifford AT, Scarlett JM, Schlafer DH. Histopathologic findings in uterine biopsy samples from subfertile bitches: 399 cases (1990-2005). J Am Vet Med Assoc 2014; 244: 180-186

Gogny A, Bruyas JF, Fiéni F. Pyometra in an inguinal hernia in a bitch. Reprod Domest Anim. 2010; 45: e461-464.

Hadley RM, Osbourne CA (1974) Canine pyometra: pathophysiology,

diagnosis and treatment of uterine and extrauterine lesions. J Amer

Anim Hosp Assoc 10: 245-268

Hadley JC (1975) Unconjugated oestrogen and progesterone

concentrations in the blood of bitches with false pregnancy and pyometra.

Vet Rec 96: 545-547

Hadley JC. (1975) The development of cystic endometrial

hyperplasia in the bitch following serial uterine biopsies. J Small

Anim Pract 16: 249-257.

Hardy RM, Osbourne CA (1974). Canine pyometra: pathophysiology,

diagnosis and treatment of uterine and extra-uterine lesions. J Amer

Anim Hosp Assoc 10: 245-268.

Veterinary Immunology and Immunopathology

Holst BS, Gustavsson MH, Lilliehöök I, Morrison D, Johannisson A (2013) Leucocyte phagocytosis during the luteal phase in bitches. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 2013, 153: 77-82

Ishiguro K, Baba E, Torii R, Tamada H, Kawate N, Hatoya

S, Wijewardana V, Kumagai D, Sugiura K, Sawada T, Inaba T. (2006)

Reduction of mucin-1 gene expression associated with increased Escherichia

coli adherence in the canine uterus in the early stage of dioestrus.

Vet J. in press

Kivisto A-K, Vasenius H, Sandholm M.(1977) Laboratory

diagnosis of canine pyometra. Acta Vet Scand 18: 308-315.

Noakes DE, Dhaliwal GK, England GCW (2001) Cystic endometrial

hyperplasia/pyometra in dogs: a review of the causes and pathogenesis.

J Reprod Fert Suppl 57: 395-406

Maddens B, Daminet S, Smets P, Meyer E (2010) Escherichia coli Pyometra Induces Transient Glomerular and Tubular Dysfunction in Dogs. J Vet Intern Med 2010 24:1263-1270

Maciel GS, Uscategui RR, de Almeida VT, Oliveira MEF, Feliciano MAR, Vicente WRR. (2014) Quantity of IL-2, IL-4, IL-10, INF-γ, TNF-α and KC-Like Cytokines in Serum of Bitches With Pyometra in Different Stages of Oestrous Cycle and Pregnancy.Reprod Dom Anim 2014; 49: 701-704

McRae GR, Coutinho da Silva MA, Runcan EE, Stephens JA, Premanandan C. Histological Studies in the Endometrium of Fertile and Subfertile Bitches. Reprod Domest Anim. 2025; 60(4): e70055.

Mir F, Fontaine E, Albaric O, Greer M, Vannier F, Schlafer DH, Fontbonne A. Findings in uterine biopsies obtained by laparotomy from bitches with unexplained infertility or pregnancy loss: an observational study. Theriogenology. 2013; 79: 312-322.

Nomura K. (1983) Canine pyometra with cystic endometrial

hyperplasia experimentally induced by E coli inoculation. Jpn J Vet

Sci 45: 237-240.

Nomura K, Kawasoe K, Shimada Y. (1990) Histological observations

of canine cystic endometrial hyperplasia induced by intrauterine scratching.

Jpn J Vet Sci 52: 979-983

Nomura K. (1994) Iinduction of a deciduoma in the dog. J Vet Med Sci

56: 365-369.

Nomura K. (1995) Histological evaluation of canine deciduoma induced

by silk suture. J Vet Med Sci 57: 9-16.

Pretzer SD (2008) Clinical presentation of canine pyometra and mucometra;

a review. Theriogenology 70: 359-363.

Rubio A, Boyen F, Tas O, Kitshoff A, Polis I, Van Goethem B, de Rooster H. Bacterial colonization of the ovarian bursa in dogs with clinically suspected pyometra and in controls. Theriogenology 2014; 82: 966-971.

Sandholm M, Vasenius H, Kivisto A-K. (1975) Pathogenesis of canine

pyometra. J Amer Vet Med Assoc 167: 1006-1010.

Schultheiss PC, Jones RL, Kesel ML, Olson PN. (1999) Normal bacterial

flora in canine and feline uteri. J Vet Diagn Invest 11: 560-562

Sevelius E, Tidholm A, Thoren-Tolling K. (1990) Pyometra in the dog.

J Amer Anim Hosp Assoc 26: 33-38.

Schlafer DH, Gifford AT. (2008) Cystic endometrial hyperplasia, pseudo-placentational

endometrial hyperplasia, and other cystic conditions of the canine

and feline uterus. Theriogenology 70: 349-358

Smith FO. (2006) Canine pyometra. Theriogenology. 66(3): 610-612.

Stone EA, Littman MP, Robertson JL, Bovee KC. (1988) Renal dysfunction

in dogs with pyometra. J Amer Vet Med Assoc 193: 457-464.

Verstegen J, Dhaliwal G,Verstegen-Onclin K. (2008) Mucometra, cystic

endometrial hyperplasia, and pyometra in the bitch: Advances in treatment

and assessment of future reproductive success. Theriogenology 70 (3

): 364 - 374

Whitney JC. (1969) The pathology of unilateral pyometra in the bitch.

J Small Anim Pract 10: 223-230.