Teratomas have several of the 3 germ cell layers - ectoderm, mesoderm

and endoderm - all within the same tumour. It is believed that they arise

from totipotent germ cells and differentiate along all pathways. The requirement

of having tissue from all 3 germ cell layers is not necessary - a minimum

of 2 is recognised as being required in Veterinary Pathology.

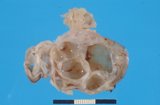

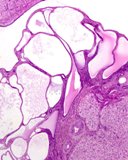

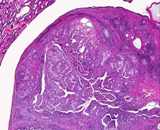

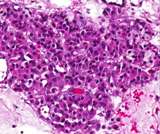

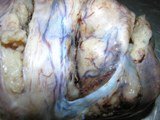

Macroscopically most are multinodular with a smooth outer contour, because

most are well differentiated and non invasive. They usually have cyst

like structures containing hair and greasy gelatinous material, and solid

areas with grey white areas, bone, translucent blue (cartilage) and black

foci.

A large ovarian teratoma in a young

bitch.

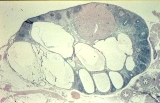

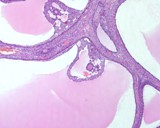

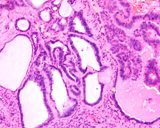

A small ovarian teratoma

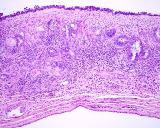

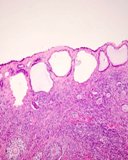

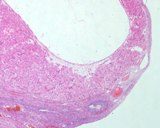

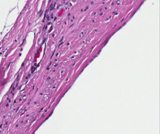

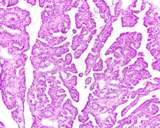

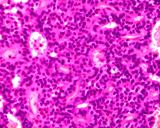

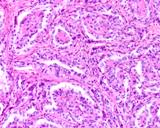

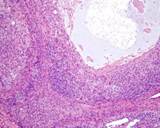

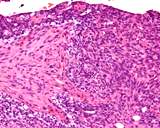

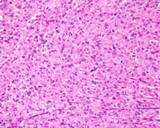

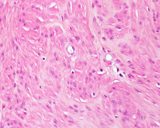

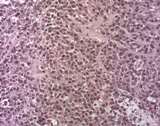

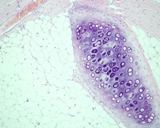

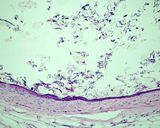

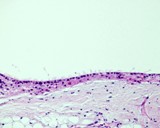

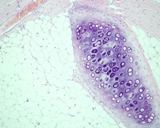

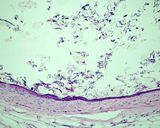

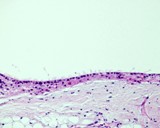

Histologically, they contain epidermis, hair, respiratory epithelium,

cartilage, bone, fat, collagen and brain and nerves and any other tissue

found in the body.

Examples of the types of tissue seen

in ovarian teratomas including, from left to right, cartilage and fat,

nervous tissue, epidermis and ciliated 'respiratory' epithelium.

Riser et al (1959) reported a single case of what they called a dermoid cyst, but which was actually a teratoma. They also had 3 other masses that contained dermoid cysts - so presumably they also were teratomas. No indication of malignancy was given.

Andrews et al (1974) reported on 2 cases of dysgerminoma. One had primitive

mesenchyma so it may have been a primitive teratoma. It was not metastatic.

Crane et al (1975) reported a malignant teratoma in a 3 yr old St Bernard. It had perioneal metastases of epithelial tissue.

Greenlee and Patniak (1985) reported seeing 7 cases of teratoma and 3

had metastasis. One had peritoneal implants and 2 had widespread metastasis.

They were from 2 to 10 cm diameter.

Patniak and Greenlee (1987) reported seeing 7 teratomas and these are

presumably the ones described in detail in Greenlee and Patniak (1985)

Rotal et al (2013) reported on a single case where the ovarian mass was in a remnant in a speyed dog. The mass was brain tissue so was considered a monophasic teratoma.

Pires et al (2019) reported on a single case of an ovarian mass which was composed of brain tissue only and thus a monophasic teratoma.

Other publications are summarised below.

Author |

# |

Age(yr) |

Benign or malignant |

Breed |

Side |

| Riser et al 1959 |

4 |

|

|

|

|

| Clayton 1975 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Crane et al 1975 |

1 |

3 |

Malignant |

St Bernard |

L |

Gruys, et al 1976 |

4 |

9, 9, 19, 11 |

Benign 2, Malignant 2 |

Var |

3L, 1R |

| Greenlee, Patnaik 1985 |

7 |

2, 3, 3, 4, 5, 9, 9 |

Benign ?, Malignant 3 |

Var |

2L, 2R |

| Trasti, Schlafer 1999 |

1 |

2 |

Malignant |

Labrador |

R |

| Nagashima et al 2000 |

1 |

2 |

benign |

Labrador |

L |

| Sforna et al 2003 |

1 |

? |

? |

? |

? |

| Yamaguchi et al 2004 |

1 |

10 |

Benign |

GSD |

R |

| Rotal et al 2013 |

1 |

5 |

Benign monophasic (brain) |

Mixed |

L |

| Pires et al (2019) |

1 |

10 |

Benign monophasic (brain) |

Boxer |

L |

Clayton HM. (1975) A canine ovarian teratoma. Vet Rec. 1975 96(26): 567-568.

Crane SW, Slocum B, Hoover EA, Wilson GP. (1975) Malignant ovarian teratoma

in a bitch. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1975 167(1): 72-74.

Greenlee PG, Patniak AK (1985) Canine ovarian tumors of germ cell origin.

Vet Pathol 1985, 22: 117-122.

Gruys E, van Dijk JE, Elsinghorst Th AM, van der Gaag I (1976) Four canine

ovarian teratomas and a nonovarian feline teratoma. Vet Pathol. 1976 13(6):

455-459.

Nagashima Y, Hoshi K, Tanaka R, Shibazaki A, Fujiwara K, Konno K, Machida

N, Yamane Y. (2000) Ovarian and retroperitoneal teratomas in a dog. J

Vet Med Sci. 2000 Jul;62(7):793-795.

Riser WH, Marcus JF, Guibor EC, Oldt CC. Dermoid cyst of the canine ovary.

J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1959 134(1): 27-28.

Sforna M, Brachelente C, Lepri E, Mechelli L (2003) Canine Ovarian Tumours:

a retrospective study of 49 cases. Vet Res Commun (2003) 27 Suppl 1: 359-361

Patnaik AK, Greenlee PG. (1987) Canine ovarian neoplasms: a clinicopathologic

study of 71 cases, including histology of 12 granulosa cell tumors. Vet

Pathol. 1987 Nov;24(6):509-14.

Pires MDA, Catarino JC, Vilhena H, Faim S, Neves T, Freire A, Seixas F, Orge L, Payan-Carreira R. Co-existing monophasic teratoma and uterine adenocarcinoma in a female dog. Reprod Domest Anim. 2019l; 54: 1044-1049.

Rota1 A, Tursi1 M, Zabarino S Appino S. (2013)

Monophasic Teratoma of the Ovarian Remnant in a Bitch. Reprod Dom Anim 2013; 48: e26–e28.

Trasti SL, Schlafer DH. (1999) Theriogenology question of the month.

Malignant teratoma of the ovary. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1999 214(6): 785-786.

Yamaguchi Y, Sato T, Shibuya H, Tsumagari S, Suzuki T. (2004) Ovarian

teratoma with a formed lens and nonsuppurative inflammation in an old

dog.

J Vet Med Sci. 2004 Jul;66(7):861-4.