The classification of canine neoplasia requires some serious consideration, with definitions for each entity. Here is a historical perspective on classification of carcinomas of the prostate. Notice I dont use the term 'carcinoma of the prostate'. Until there is consensis about what is adenocarcinoma and what is urothelial carcinoma (the new term for transitional cell carcinoma), doubt will remain.

O'Shea (1968) classified

6 of 7 to be adenocarcinoma, while 1 was classified as a urothelial carcinoma.

Leav and Ling (1968) divided carcinomas into adenocarcinoma (intraalveolar and small acinar types) and undifferentiated adenocarcinoma (syncytial and descrete epithelial types).

Cornell et al (2000) examined 76 cases in detail and divided canine prostate carcinoma into adenocarcinoma, urothelial carcinoma, squamous carcinoma and mixed carcinoma, on morphological grounds. The criteria for each was lacking. The majority of theirs were considered mixed or adenocarcinomas.

LeRoy et al (2004) used the Leav and Ling (1968) classification. They compared carcinomas in the prostate with urothelial carcinomas of the bladder. Both had similar patterns.

Lai et al (2008) examined 20 cases and divided the carcinomas into micropapillary, cribriform, solid, sarcomatoid, small acinar/ductal and tubulopapillary patterns. They noted that mixed patterns occurred in 15 of 20 cases and all in the same cross section.

Palmieri et al (2014) had 50 carcinomas and 31 (62%) were of a single type, either small acinar/ductal, solid, cribriform (with or without comedonecrosis), or papillary (with or without comedonecrosis). The remainder (19 or 38%) were mixed with one or more of the patterns. These authors expanded the types of carcinoma of the prostate and their types were papillary, cribriform, solid, and small acinar/ductal types. They also noted sarcomatoid, signet ring, and mucinous types. Dogs with urothelial carcinoma of the bladder were excluded.

Ackers et al (2015) studied carcinomas of the prostate of 34 dogs using staining for androgen receptor, CK8 and CK18 for luminal cells and CK5 and CK14 for basal cells. They considered them all adenocarcinoma and identified 4 types of tumor - cribriform, solid, small acinar/ductal and micropapillary types.

de Brot et al (2022) reported on the division of their 41 cases into adenocarcinoma (10/41), urothelial carcinoma 21/41), and mixed carcinoma (9/41). p63 staining was positive in 24/40. The staining patterns for p63, HMWCK, Uroplakin III and NSE were reported by not consistent for histological classification. They had many cases with an intraductal component that they considered unique to their study; however carcinoma in situ is reported - as neoplasia within ducts in prostates with carcinoma.

So what is the bottom line with classification in my humble opinion (IMHO)?

- Urothelial carcinoma of the pelvic urethra and proximal prostatic ducts occur, and the patterns can be identical to those of adenocarcinomas.

- It makes more sense that dogs neutered as puppies are more likely to develop urothelial or ductal carcinomas.

- Location and growth habit of the carcinoma is important in differentiating urothelial from adenocarcinoma

- Until there is a prognostic difference identified between the various types, the generic term 'carcinoma of the prostate' or 'prostate carcinoma' be used (with prostate being a descriptive noun). Prostatic carcinoma is ok too.

- Many carcinomas have a mixed phenotype (as they do in humans).

- Subdividing carcinoma of the prostate into types is a research tool. Until better ways of defining urothelial and glandular types is available, the basic division of carcinomas should be Urothelial, mixed urothelial and adenocarcinoma, adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma.

- Terminology of the subtypes of adenocarcinoma and urothelial carcinoma should reflect the human terminology

- The terminology used in the review paper by Palmieri et al (2019) is a good start

Consensis classificiation based on Palmieri et al (2019) (yes I was involved)

1. Urothelial carcinoma:

- solid,

- papillary,

- cribriform (with and without necrosis)

2. Adenocarcinoma:

- simple tubular

- papillary

- cribriform

- solid

3. Carcinoma with mixed urothelial and glandular phenotypes

de Brot S, Lothion-Roy J, Grau-Roma L, White E, Guscetti F, Rubin MA, Mongan NP. Histological and immunohistochemical investigation of canine prostate carcinoma with identification of common intraductal carcinoma component. Vet Comp Oncol. 2022; 20: 38-49.

Palmieri C, Foster RA, Grieco V, Fonseca-Alves CE, Wood GA, Culp WTN, Murua Escobar H, De Marzo AM, Laufer-Amorim R. Histopathological Terminology Standards for the Reporting of Prostatic Epithelial Lesions in Dogs. J Comp Pathol 2019; 171: 30-37

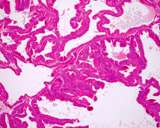

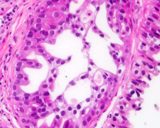

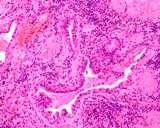

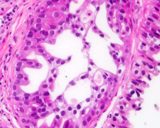

Figure : Prostate carcinoma

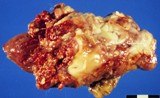

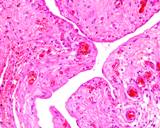

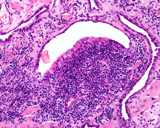

Figure : Prostate carcinoma

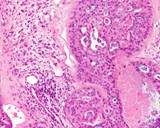

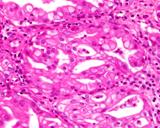

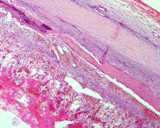

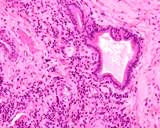

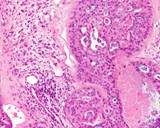

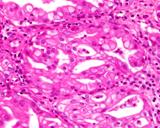

Figure : Prostatic carinoma

Grieco et al (2003) looked at 11 carcinomas

- one squamous cell carcinoma, 7 adenocarcinomas and 3 undifferentiated.

All stained with AE1/AE3 and with vimentin 3B4. 10 stained with CK8-12 (for luminal cells) and 6 coexpressed CK14

(for basal cells). They suggested that coexpresion of luminal and basal cell types indicate an epithelial stem cell phenotype.

Lai et al (2008) examined carcinoma of the prostate using HMWCK (CK 1, 5, 10 and 14), CK 5, CK7, CK14 and CK 18, uroplakin III, prostatic specific antigen and prostate specific membrane antigen. Of all 20 tumors examined, all stained for CK18, 17 for CK7, 13 for CK5, 12 for CK14 and uroplakin, 11 for HMWCK, 10 for PSMA and 8 for PSA. This compares with the staining characteristics of normal gland, prostatic duct and urothelium. In intact dogs, luminal acinar cells were all PSA and CK18+. 2 of 8 were CK7+. Basal acinar cells were HMWCK (2/8) + and CK5+ (5/8). Prostatic ducts were mostly CK18+ (8/8 for periurethral and 7/8 for peripheral duct), and all were negative for UPIII. 6/8 were positive for PSA. The luminal urothelium was UPIII (all), CK5 (all) PSA (6/8), CK5 (6/8) positive. basal urothelial cells were UPIII negative but most w ere HMWCK and CK5 positive. In castrated dogs (2 cases), the urethra was identical to the intact dogs. Only ducts were present in the prostate and they all stained for PSA, PSMA, and CK18. The periurethral tubules stained for CK7.

The origin of the various carcinomas has been debated for many years.

Weaver (1981) indicated that it was impossible to differentiate primary

prostatic carcinoma from transitional cell carcinoma. LeRoy et al (2004)

attempted to use a less subjective method than morphological features

by using techniques to identify cytokeratin 7 and arginine esterase, but

could not differentate between the major types. There are no consistent

immunohistochemical markers for prostatic carcinomas. As both cell types

(glands) arise from a common progenitor, it is not surprising! Normal

and hyperplastic prostate stains for Prostatic specific antigen (PSA),

PSA protein (PSEP) and for Canine prostatic antigen.

In the 31 cases examined

by McEntee et al (1987) only 8 stained for canine prostatic antigen, 2

stained form PSA and 3 stained for PSAP.

LeRoy et al (2007) investigated potential phenotypes of carcinoma of

the prostate by comparing protein expression profiling. They examined

carcinomas from 3 dogs and compared from 789 to 1305 proteins from these

and from normal bladder and prostatic epithelia from 6 dogs. There was

no clear similarity of protein expression between the neoplasms and normal

tissues and it appeared as thought the protein expression of the neoplasms

was different and unique to the protein expression of the normal tissues.

Lai et al (2008) wrote a series of papers that involved immunohistochemical staining of normal prostates from castrated and intact dogs, and from 20 dogs with spontaneous prostate tumours. 11 of these dogs were neutered and nine were intact. They stained the tissues with cytokeratins HMWCK, CK5, CK7, CK14, and CK18, uroplakin III, prostate specific antigen (PSA) and prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA). They classified the carcinomas into six groups: – solid, cribriform, micropapillary, sarcomatoid, small acinar/ductal and tubulopapillary. Eight of 20 stained with PSA, 10 of 20 stained with PSMA, 17 of 20 stained with uroplakin III, 12 with CK7, 11 of 20 stained with HMWCK, 13 with CK 5, 12 with CK 14 and 20 express CK 18. Their interpretation was that prostatic carcinomas most likely originate from collecting ducts and that the canine disease resembled human androgen refractory poorly differentiated carcinoma.

Ackers et al (2015) then examined the dogs reported by Palmieri et al (2014) and attempted to determine if the origin of the neoplastic cell was a basal, intermediate or luminal cell. This of course assumes that the carcinomas are adenocarcinomas, and arise in the glandular tissue. Their control tissue was acini of normal and hyperplastic prostates. They used basal cell markers (CK 5 and CK 14), luminal markers (androgen receptor, CK 8 and 18) and intermediate cells (of basal region CK5+ CK14, or intermediate cells of the

luminal layer CK 5 and CK 18 coexpression). They could not consistently get p63 to work. They only selected the prostatic carcinomas with a single and not a mixed phenotype. The neoplasms had a variety of staining patterns. They found a predominance of staining as would be expected in luminal cell types (AR, CK8 and CK18). As with their previous paper, there was no indication of neuter status or the dogs.

| |

|

|

|

Basal cell |

Basal cell |

|

luminal cell |

luminal cell |

? acinar |

|

urothelium |

| |

Vimentin |

PanCK |

HMWCK

(1, 5 |

CK5 |

CK14 |

CK7 |

CK8 |

CK18 |

AR |

PSA |

Uroplakin III |

| McEntee 1987 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Greico et al (2003) |

11/11 |

11/11 |

|

1/11 |

6/11 |

|

10/11 |

|

|

|

|

| Lai et al (2008) |

|

|

11/20 |

13/20 |

12/20 |

17/20 |

|

20/20 |

|

10/20 |

12/20 |

| Lai et al (2009) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

16/20 |

|

|

| Ackers et al (2015) |

|

|

|

25/34 |

20/34 |

|

33/34 |

33/34 |

34/34 |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Occurrence of metastatis:

Leav and Ling (1968) found metastases in 20 of their 20 dogs.

Cornell et al (2000) found metastasis in 80% of their 76 cases

Palmieri et al (2014) reported 12 out of 50 (24%) cases were metastatic.

Ravicini et al (2018) reported on 67 affected dogs. 60 were castrated and 7 were intact. 26 had metastasis - lymph nodes in 19, lungs in 10, and bone in 2. Median survival overall was 82 (7-752 days). With NSAIDS and chemotherapy, the MST was 106 days, and 51 days in dogs without therapy.

Location of metastasis

Palmieri et al (2014) reported that the common sites were lung, lymph node and kidney. No boney involvement was reported.

A diagnosis of prostate carcinoma in a dog carries an extremely poor

prognosis. Many have metastasis at diagnosis - to 100% is reported. Many will develop metatasis unless they succumb to local disease first. Metastasis is

to the lung and local lymph node, and about 7 to 14% have metastasis to bone, especialy

the lumbar vertebrae and pelvis (Leav and Ling 1968, Durham and Dietze

1986, Cornell et al 2000).

Rodrigues et al (2011) suggests that vimentin expression by a prostatic carcinoma indicates a progression to a maligancy phenotype. They identified changes they considered to be prostatic inflammatory atrophy, prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN) and invasive carcinoma. Considering the dogma that canine prostates do not develop low and intermediate grade PIN and that the photomicrographs provided in the publication are not convincing, I suggest this be accepted with caution and that it requires substantiation. Positive staining for vimentin of the epithelial cells is known in prostatic carcinomas, and as all prostatic carcinomas are malignant (or are believed to be so), it is not surprising that this study found vimentin associated with a malignant phenotype.

Pathogenesis

There are no known causes, although there is a slightly increased risk

in castrated dogs (Teske et al 2002). As already indicated, castration

is not protective so the systemic hormonal environment does not appear

to be important. Lai et al (2009) looked at this further and found that

androgen receptors were less common in neoplastic prostatic tissue than

in normal prostate. Postive staining was in the cytoplasm rather than

the nucleus and there was no detectable mutations to DNA coding for the

androgen receptor.

There are numerous studies outlining the distribution of estrogen receptors

in canine prostates, and the intranuclear receptors are found in stromal

cells and in the epithelial cells. Hyperplastic prostates have a similar

distribution. Grieco et al (2006) found a loss of estrogen receptors in

the stromal of all prostates including those with carcinoma. The main

ER in the epithelium is ERBeta. In the more 'differentiated' tumours,

ER was present but with less intense staining. Staining was reduced with

the less differentiated tumours. The significance of this is yet to be

established. Gallardo et al (2007) examined androgen receptor, estrogen

alpha and beta, and progesterone receptor expression in prostatic specimens

from dogs with prostatic hyperplasia, prostatatitis and neoplasia. Expression

of these were less common in disease except for progesterone receptor,

where more animals had expression in disease conditions.

Palmieri and Riccardi (2013) reported on the presence of the homeobox gene HOXA13 in normal, hyperplastic and neoplastic prostatic tissue and found it in all cases but much more prevalent in carcinoma of the prostate.

Prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia. It is widely believed that

precursor lesions, such as low grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia

(PIN), do not occur in dogs. High grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia

is seen, and often in prostates with neoplasia. Waters and Bostwick (1997)

report the presence of high grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia

in dogs. They examined 35 prostates from dogs without clinical evidence

of prostatic disease. They found high grade PIN in 1 of 13 dogs less than

4 years, and 6 of 11 dogs from 7 to 11 years old, and in 1 of 11 dogs

that had been castrated. Waters et al (1997) found high grade PIN in19

of 29 prostates with carcinoma. Madewell et al (2004) examined canine

prostates for high grade PIN. No examples were seen in 20 normal prostate

glands or in 95 glands from dogs with prostatic hyperplasia. High grade

PIN was found in 7 of 20 prostates with carcinoma. Matsuzaki et al (2010)

claims to have 5 cases of PIN and examined them by immunohistochemistry.

They believe these to be low grade PIN, thus drawing a parallel with the

human disease. This study is therefore contradictory to the widely held

view of the lack of low grade PIN in dogs. The foci in their study had

a higher expression of nuclear p63 and a higher proliferation index (PCNA)

than normals. These cells had 'heterogenous' staining with androgen receptor.

They surmised that basal cells play a role in the development of canine

PIN.

Some prostatic carcinomas have cytogenetic abnormalities and of particular

interest is one with a similar abnormality to a human prostatic carcinoma.

The carcinoma studies had trisomy of chromosome 13, which is similar to

chromosome 8 of humans and which also has cytogenetic anomalies in some

human prostatic carcinomas (Winkler et al 2006). This is a recent field

of investigaton with the first report being by Winkler et al (2005).

Palmieri (2015) found that carcinomas in the prostate acquire expression of angiogenic factors such as PECAM-1, VEGF and FGF-2.

Akter SH, Lean FZ, Lu J, Grieco V, Palmieri C. Different Growth Patterns of Canine Prostatic Carcinoma Suggests Different Models of Tumor-Initiating Cells. Vet Pathol. 2015 52(6):1027-1033.

Bell RW, Klausner JS, Hayden DW, Feeney DA, Johnston SD (1991) Clinical

and pathologic features of prostatic adenocarcinoma in sexually intact

and castrated dogs: 31 cases (1970-1987). J Amer Vet Med Asoc 199: 1623-

Cornell KK, Bostwick DG, Cooley DM, Hall G, Harvey HJ, Hendrick MJ, Pauli

BU, Render JA, Stoica G, Sweet DC, Waters DJ. (2000) Clinical and pathologic

aspects of spontaneous canine prostatic carcinoma: a retrospective analysis

of 76 cases. The Prostate 45: 173-183.

Durham SK, Dietze AE (1986). Prostatic adenocarcinoma with and without

metastasis to bones in dogs. J Amer Vet Med Assoc 188: 1432-1436.

Gallardo F, Mogas T, Baró T, Rabanal R, Morote J, Abal M, Reventós

J, Lloreta J. (2007) Expression of Androgen, Oestrogen a and ß,

and Progesterone Receptors in the Canine Prostate: Differences between

Normal, Inflamed, Hyperplastic and Neoplastic Glands J Comp Path 136:

1-8

Grieco V, Patton V, Romussi S, Finazzi M. (2003) Cytokeratin and vimentin

expression in normal and neoplastic canine prostate. J Comp Path 129:

78-84.

Grieco V, Riccardi E, Rondena M, Romussi S, Stefanello D, Finazzi M.

(2006) The distribution of oestrogen receptors in normal, hyperplastic

and neoplastic canine prostate, as demonstrated immunohistochemically.

J Comp Pathol. 135(1):11-16.

Guerin VJ, Visser 't Hooft KW, L'Eplattenier HF, Petite AF (2012) Transitional cell carcinoma involving the ductus deferens in a dog. J Amer Vet Med Assoc 2012, 240: 446-449

Lai C-L, van den Ham R, van Leenders G,

van der Lugt J, and Teske E. (2008) Comparative characterization of the canine normal prostate in intact and castrated animals.The Prostate 2008; 68: 498-507

Lai C-L, van den Ham R, van Leenders G,

van der Lugt J, Moll JA, and Teske E. (2008) Histopathological and immunohistochemical characterisation of canine prostate cancer.The Prostate 2008; 68: 477-488

Lai C-L, van den Ham R, Mol J, Teske E (2009) Immunostaining of the androgen

receptor and sequence analysis of its DNA-binding domain in canine prostate

cancer. The Vet J 181: 256-260

Leav I, Ling GV. (1968) Adenocarcinoma of the canine prostate. Cancer

22: 1329-1345.

LeRoy BE, Nadella MVP, Toribio RE, Leav I, Rosol TJ. (2004) Canine prostate

carcinomas express markers of urothelial and prostatic differentiation.

Vet Pathol 41: 131-140.

LeRoy BE, Painter A, Sheppard H. Popiolek L, Samuel-Foo M, Andacht TM.

(2007) Protein expression profiling of normal and neoplastic canine prostate

and bladder tissue. Vet Comp Oncology 5 (2) 119-130.

Madewell BR, Gandour-Edwards R, DeVere White RW. (2004) Canine prostatic

intraepithelial neoplasia: is the comparative model relevant? The Prostate

m58: 314-317.

McEntee M, Isaacs W, Smith C. (1987) Adenocarcinoma of the canine prostate:

immunohistochemical examination for secretory antigens. The Prostate 11:

163-170.

Matsuzaki P, Cogliati B, Sanches DS, Chaible LM, Kimura KC, Silva TC,

Real-Lima MA, Hernandez-Blazquez FJ, Laufer-Amorim R, Dagli MLZ (2010)

Immunohistochemical Characterization of Canine Prostatic Intraepithelial

Neoplasia. J Comp Path 142: 84-88

O'Shea JD (1963) Studies on the canine prostate gland. II Prostatic neoplasms.

J Comp Path 73: 244-252

Palmieri C, Lean FZ, Akter SH, Romussi S, Grieco V. A retrospective analysis of 111 canine prostatic samples: histopathological findings and classification. Res Vet Sci. 2014; 97: 568-573.

Palmieri C, Riccardi

E. (2013) Immunohistochemical Expression of HOXA-13 in Normal, Hyperplastic and Neoplastic Canine Prostatic Tissue. J Comp Pathol 2013; 149: 417–423

Palmieri C. Immunohistochemical Expression of Angiogenic Factors by Neoplastic Epithelial Cells Is Associated With Canine Prostatic Carcinogenesis. Vet Pathol. 2015; 52: 607-613.

Ravicini S, Baines SJ, Taylor A, Amores-Fuster I, Mason SL, Treggiari E. Outcome and prognostic factors in medically treated canine

prostatic carcinomas: A multi-institutional study. Vet Comp Oncol 2018: 1-9

Rodrigues MMP, Rema A, Gärtner F, Soares FA, Rogatto SR, De MourVMBD, Laufer-Amorim R. (2011) Overexpression of Vimentin in Canine Prostatic Carcinoma. J Comp Path 2011 144: 308-311

Taylor PA (1973) Prostatic adenocarcinoma in a adog and a summary of

ten cases. Canadian Vet J 14: 162-166.

Teske E, Naan EC, van Dijk EM, Van Garderen E, Schalken JA. (2002) Canine

prostate carcinoma: epidemiological evidence of an increased risk in castrated

dogs. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2002 197(1-2):251-255

Waters DJ, Bostwick DG. (1997) Prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia occurs

spontaneously in the canine prostate. J Urol 157: 713-716.

Waters DJ, Hayden DW, Bell FW, Klausner JS, Qian J, Bostwick DG. (1997)

Prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia in dogs with spontaneouos prostate

cancer. (The Prostate 30: 92-97.

Weaver AD (1981) Fifteen cases of prostatic carcinoma in the dog. Vet

Rec 109: 71-75.

Winkler S, Murua Escobar H, Eberle N, Reimann-Berg N, Nolte I, Bullerdiek

J. (2005) Establishment of a cell line derived from a canine prostate

carcinoma with a highly rearranged karyotype. J Hered. 96(7):782-785.

Winkler S, Reimann-Berg N, Escobar HM, Loeschke S, Eberle N, Hoinghaus

R, Nolte I, Bullerdiek J. (2006) Polysomy 13 in a canine prostate carcinoma

underlining its significance in the development of prostate cancer. Cancer

Genet Cytogenet.169(2):154-158