Cystic endometrial hyperplasia has been reviewed by several authors (Agudelo 2004). Cystic endometrial hyperplasia in the cat has almost always been thought to be similar to the disease in the bitch, but this may not be so. There are sufficient differences both in the disease and in the normal physiology of the 2 species to suggest they are not as similar as suspected.

Pathogenesis

Normal cyclic changes in the endometrium are under the control of ovarian steroidal hormones including oestrogen and progesterone. Physiological hyperplasia of the endometrium occurs during the luteal phase of the cycle and subsequent atrophy occurs during anoestrus. Ovarian androgens, produced by the theca interna may also play a role, and, while their function and control is not known, ovarian interstitial endocrine cells may play a role in this (Perez et al 1999). Oestrogen have a 'priming' function that allows the cells to respond fully to progesterone. Progesterone, though, alone will cause endometrial hyperplasia (Thornton and Kear 1967, Boomsma et al 1982, Chatdarong et al 2005)

Perez et al (1999) reported that feral queens did not have cystic endometrial hyperplasia, and their serum oestrogen concentration was lower during anoestrus than colony-reared queens. Feral queens also have more interstitial endocrine cells of the ovary. The control mechanisms involved are not known. The reproductive status of the feral cats, apart from them being mature animals, was unknown either.

Correlating concentrations of oestrogen and progesterone with degrees of hyperplasia, or with hyperplasia in general has been problematic, suggesting that local factors such as receptor concentration or the concentration of local endometrial growth factors may be more important. Boomsma et al (1997) examined feline endometrium for the presence of transforming growth factor, epidermal growth factor (EGF) and EGF receptor, and found them in the epithelium and stroma. Misirlioglu et al (2006) examined 10 normal cats and 20 cats with cystic endometrial hyperplasia and pyometra. They found that the endometrial hyperplasia group could be divided into 2 subgroups - those with mild hyperplasia and those with marked hyperplasia. They found that oestrogen receptor (ER) expression was lower in the mild hyperplasia group and higher in marked hyperplasia. c-erb-2 oncoprotein expression was also increased in both hyperplasia groups, as compared to controls. Progesterone receptors were lower in the hyperplastic groups than in controls.

Dow (1962) reported on 91 female cats with endometrial hyperplasia, uterine polyps and endometritis and pyometra. There were 20 cats with hyperplasia but no evidence of inflammation (9 also had polyps), 29 cats with endometrial hyperplasia and acute endometritis and pyometra (2 had polyps), 10 had 'subacute endometritis', and 22 had chronic endometritis While many affected cats had corpora lutea, some did not. The assumption is therefore that cats with endometrial hyperplasia are more prone to developing infection and inflammation.

Potter et al (1991) examined 79 queens with either clinical disease or lesions found at surgery or necropsy. 31 queens had clinically silent lesions of the uterus. 43 cats had never been bred, and 25 had clinical signs. All 79 cats had endometrial hyperplasia, 30 had pyometra, 10 had endometritis only, 21 had uterine polyps, and 5 had adenomyosis. 11 had cystic follicles, 6 had parovarian cysts, and 11 had cystic rete ovarii. Those with endometreal hyperplasia usually had some degree of uterine luminal dilation. They concluded that endometrial hyperplasia was seen mostly in older cats (>5yrs) and was a function of age in cats. Only 25 of the 79 cats with endometrial hyperplasia had a corpus luteum, so they surmised that hyperplasia was a function of oestrogen stimulation and not progesterone.

Based on these and subsequent findings, the general pathogenesis is assumed to be that the development of endometrial hyperplasia is related to hormonal and environmental factors. The effect of foreign material (i.e. infection) stimulating endometrial hyperplasia, as occurs in the dog, is unknown.

Macroscopic appearance

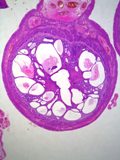

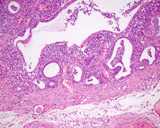

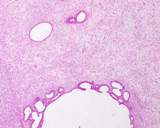

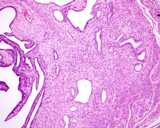

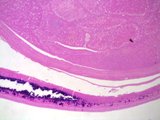

A uterus with endometrial hyperplasia is thicker and more convoluted than normal. In severe cases, this is especially visible on cross section where the corkscrew shape of the lumen is exaggerated and cysts are visible.

Figure : Endometrial hyperplasia. The normal corkscrew appearance of the endometrium is exaggerated and there is cystic dilation of the lumen (mucometra) and dramatic thickening of the endometrium.

Microscopic appearance

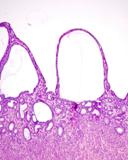

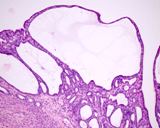

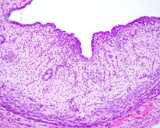

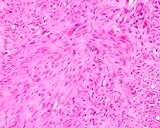

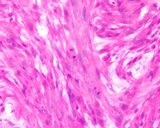

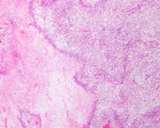

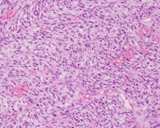

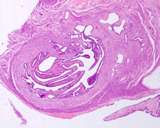

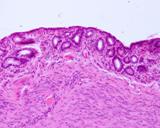

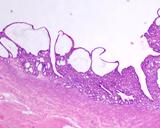

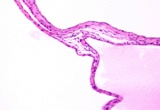

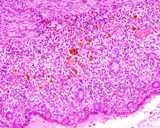

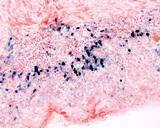

Histological changes in the endometrium with hyperplasia varies from mild to severe. Mild hyperplasia is a thickening of the endometrium with elongation of the glands. As this becomes more greater, the glands become disorganised and rather than straight, become convoluted so that the cross sections vary. The stroma becomes more prominent. There is dilation of the glands with the formation of variably sized cysts.

Figure : Cystic endometrial hyperplasia.

Agudelo CF. (2005) Cystic endometrial hyperplasia-pyometra complex in cats. A review. Vet Q. 27(4):173-182.

Boomsma RA, Jaffe RC, Verhage HG (1982) The uterine progestational response to cats: changes in morphology and progesterone receptors during chronic administration of progesterone to estradiol-primed and nonprimed animals. Biol Reprod 26: 511-521.

Boomsma RA, Mavrogianis PA, Verhage HG. (1997) Immunocytochemical localization of transforming growth factor a, epidermal growth factor and epidermal growth factor receptor in the cat endometrium and placenta. Histochemical J 29:495-504.

Chatdarong K, Rungsipipat A, Axner E, Linde Forsberg C. (2005) Hysterographic appearance and uterine histology at different stages of the reproductive cycle and after progestagen treatment in the domestic cat. Theriogenology. 64(1):12-29.

Dow C (1962). The cystic endometrial hyperplasia - pyometra complex in the cat. Vet Rec 74: 141-147.

Misirlioglu D, Nak D, Sevimli A, Nak Y, Ozyigit MO, Akkoc A, Cangul IT. (2006) Steroid receptor expression and HER-2/neu (c-erbB-2) oncoprotein in the uterus of cats with cystic endometrial hyperplasia-pyometra complex. J Vet Med A Physiol Pathol Clin Med. 53(5):225-229.

Perez JF, Conley AJ, Dieter JA, Sanz-Ortega J, Lasley BL (1999) Studies on the origin of ovarian interstitial tissue and the incidence of endometrial hyperplasia in domestic and feral cats. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 116(1):10-20.

Potter K, Hancock DH, Gallina AM (1991) Clinical and pathological features of endometrial hyperplasia, pyometra and endometritis in cats: 79 cases (1980-1985). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 198(8):1427-1431.

Thornton DAK, Kear M (1967). Uterine cystic hyperplasia in a siamese cat following treatment with medroxyprogesterone. Vet Rec 80: 380-381.